JUST A FEW SLAVIC LOANWORDS IN ALBANIAN LANGUAGE

Origins of Albanian language and ethnos

Collapse

X

-

Carlin, many of those words are quite fundamental and would typically not be the kinds of words that a language would need to use a loan word for (other than kastravec I guess). What is the significance of noting these loan words in the Albanian language in your opinion?Risto the Great

MACEDONIA:ANHEDONIA

"Holding my breath for the revolution."

Hey, I wrote a bestseller. Check it out: www.ren-shen.com

Comment

-

-

Thanks for your question.Originally posted by Risto the Great View PostCarlin, many of those words are quite fundamental and would typically not be the kinds of words that a language would need to use a loan word for (other than kastravec I guess). What is the significance of noting these loan words in the Albanian language in your opinion?

If I can count correctly, I only provided 10 words which is but a small sample of Slavic loanwords (in Albanian).

For those who are more eager to continue I provide the following link -

alcune pagine non sono venute bene durante la scannerizzazione e alcune mancano per intero, ma meglio che niente

So, why do languages have loanwords?

Per Prof. S. Kemmer from Rice University:

Borrowing is a consequence of cultural contact between two language communities. Borrowing of words can go in both directions between the two languages in contact, but often there is an asymmetry, such that more words go from one side to the other. In this case the source language community has some advantage of power, prestige and/or wealth that makes the objects and ideas it brings desirable and useful to the borrowing language community. For example, the Germanic tribes in the first few centuries A.D. adopted numerous loanwords from Latin as they adopted new products via trade with the Romans. Few Germanic words, on the other hand, passed into Latin.

The actual process of borrowing is complex and involves many usage events (i.e. instances of use of the new word). Generally, some speakers of the borrowing language know the source language too, or at least enough of it to utilize the relevant words. They adopt them when speaking the borrowing language. If they are bilingual in the source language, which is often the case, they might pronounce the words the same or similar to the way they are pronounced in the source language. For example, English speakers adopted the word garage from French, at first with a pronunciation nearer to the French pronunciation than is now usually found. Presumably the very first speakers who used the word in English knew at least some French and heard the word used by French speakers.

Encyclopedia Britannica further states:

Languages borrow words freely from one another. Usually this happens when some new object or institution is developed for which the borrowing language has no word of its own.

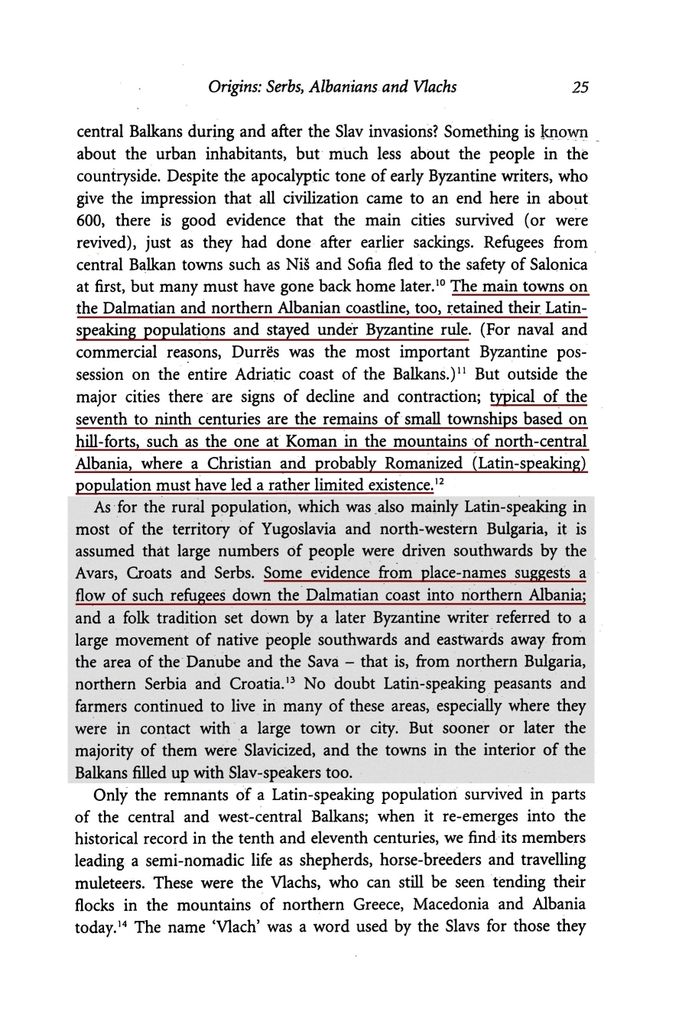

If we consider, like you pointed out, that the majority of these words are quite fundamental it appears self-evident that the contact between Slavic-speakers and Albanian-speakers happened at a very early stage.

More importantly, some questions arise:

1) Did the source language community (Slavic-speakers) have some advantage of power, prestige and/or wealth over the borrowing language community (Albanian-speakers) at this unspecified early time / stage? (If it was not power or prestige do we then have to consider and explore the possibility that the Albanians arrived to the Balkans after the Slavs? Were the Mardaites these early Albanians? Regardless of wealth or prestige, can we simply ignore the argument that the Albanians arrived from elsewhere?)

2) Did some number of early Albanian-speakers also speak Slavic?

3) Did the borrowing language have no native words/terms for the numerous fundamental words specified?Last edited by Carlin; 03-15-2017, 09:06 PM.

Comment

-

-

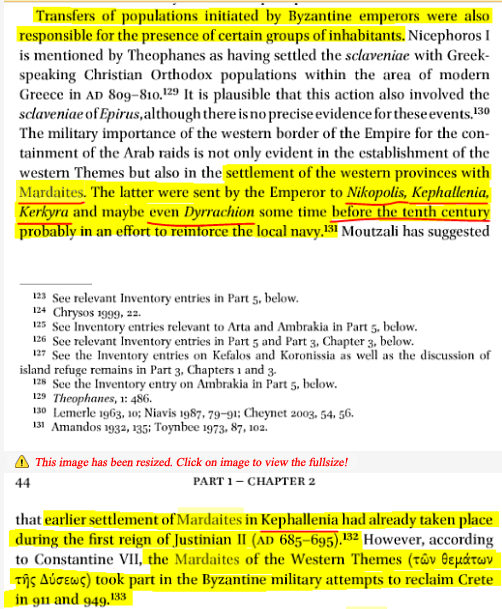

The Umayyads were compelled to sign another treaty by which they paid the Byzantines half the tribute of Cyprus, Armenia and the Kingdom of Iberia in the Caucasus Mountains; in return, Justinian relocated around 12,000 Mardaites to the southern coast of Anatolia, as well as parts of Greece such as Epirus and the Peloponnese, as part of his measures to restore population and manpower to areas depleted by earlier conflicts.

So :

1. Mardaites were 12,000 who settled in many part of Epirus including the very southern parts. Also in Anatolia and Peloponnese. The number of Mardaites in the Albanian territory was very insignificant to create a new nation. We also know that Albanians expanded themselves from the north to the south by the 15th century.

2. Mardaites were taken to restore the population in the Byzantine Empire so why would 1/5 or 1/6 evolve into a nation?

3. Chances are that Albanians came even later than Mardaites in this territory seeing as the toponyms are expected to come from the Bulgarian occupation.Last edited by tchaiku; 03-16-2017, 12:27 PM.

Comment

-

-

1. 12,000 was very likely a 'stock figure'. It could have been less, or more. The number is high enough for a warrior/power elite to assert themselves (under the blessing and support of Byzantine/Roman government structures), form the ruling class in certain regions and subsequently influence and linguistically assimilate the local population. How many Frenchmen were necessary in order to influence and change the speech of the Anglo-Saxon population of England? How many Englishmen were required to totally eclipse the native tongue of Scotland?Originally posted by tchaiku View PostThe Umayyads were compelled to sign another treaty by which they paid the Byzantines half the tribute of Cyprus, Armenia and the Kingdom of Iberia in the Caucasus Mountains; in return, Justinian relocated around 12,000 Mardaites to the southern coast of Anatolia, as well as parts of Greece such as Epirus and the Peloponnese, as part of his measures to restore population and manpower to areas depleted by earlier conflicts.

So :

1. Mardaites were 12,000 who settled in many part of Epirus including the very southern parts. Also in Anatolia and Peloponnese. The number of Mardaites in the Albanian territory was very insignificant to create a new nation. We also know that Albanians expanded themselves from the north to the south by the 15th century.

2. Mardaites were taken to restore the population in the Byzantine Empire so why would 1/5 or 1/6 evolve into a nation?

3. Chances are that Albanians came even later than Mardaites in this territory seeing as the toponyms are expected to come from the Bulgarian occupation.

(Also, it is true that the Albanians expanded themselves from the north to the south by the 15th century. Even Phrantzes, in his own time, asserted the following:

“Half of Peloponnese land was actually occupied by the Albanians at that time and they attempted to get the other half, too, both by force of arms and by negotiation with Sultan Mehmed II.”)

2. If Mardaites were indeed taken to restore the population in certain regions of the Byzantine Empire, this can only mean that these regions and districts were either totally depopulated or very sparsely inhabited. Why would they not evolve into a "nation"?

3. Fair enough. This is possible.

Comment

-

-

It is a fact that Mardaites were taken to restore the population in many regions:Originally posted by Carlin View PostIf Mardaites were indeed taken to restore the population in certain regions of the Byzantine Empire, this can only mean that these regions and districts were either totally depopulated or very sparsely inhabited. Why would they not evolve into a "nation"?

Many parts of Peloponnese

Many part of Turkey

Many part of Epirus

This book presents the first analytical account in English of major developments within Byzantine culture, society and the state in the crucial formative period from c.610-717. The seventh century saw the final collapse of ancient urban civilization and municipal culture, the rise of Islam, the evolution of patterns of thought and social structure that made imperial iconoclasm possible, and the development of state apparatuses--military, civil and fiscal--typical of the middle Byzantine state. Also, during this period, orthodox Christianity finally became the unquestioned dominant culture and a religious framework of belief (to the exclusion of alternative systems, which were henceforth marginalized or proscribed).

So it does not add up to me.

Comment

-

-

That's fine. The fact remains that many Mardaites were settled in these parts, even though we do not know the specifics or precise numbers.Originally posted by tchaiku View PostIt is a fact that Mardaites were taken to restore the population in many regions:

Many parts of Peloponnese

Many part of Turkey

Many part of Epirus

This book presents the first analytical account in English of major developments within Byzantine culture, society and the state in the crucial formative period from c.610-717. The seventh century saw the final collapse of ancient urban civilization and municipal culture, the rise of Islam, the evolution of patterns of thought and social structure that made imperial iconoclasm possible, and the development of state apparatuses--military, civil and fiscal--typical of the middle Byzantine state. Also, during this period, orthodox Christianity finally became the unquestioned dominant culture and a religious framework of belief (to the exclusion of alternative systems, which were henceforth marginalized or proscribed).

So it does not add up to me.

Even if Mardaites were/are not 'proto-Albanian speakers' the question remains, what was the ethnological impact of Mardaites in Epirus, Peloponnese and other districts? Did the Albanians absorb and assimilate the Mardaites?

For Thomas Gordon, who wrote "History of the Greek Revolution: In Two Volumes, Volume 1" the settlement of Mardaites (in Epirus, Peloponnese) was due to the fact that great part of the population was exterminated (pg. 7 and 8):

"We only know that proper Greece was repeatedly and cruelly wasted by Goths, Saracens, and Bulgarians, that her cities were mostly ruined, great part of the population exterminated, and that to fill up the void, the emperors planted there, at various periods, colonies of Mardaites and Sclavonians."

Comment

-

-

Influence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the Creation of the Albanian Nation (1896-1908)

Разбијмо режимски медијски мрак - будимо сви ФБ репортери

Разбијмо режимски медијски мрак - будимо сви ФБ репортери

Namely, the doctoral thesis of the recently deceased Bulgarian historian Teodora Toleva (1968-2011) in Spanish under the original title in Spanish La influencia del Imperio Austro-Hungaro en la construccion nacional albanesa (1896-1908), in which she in a factographically rich book divided into ten chapters explains her vision of the genesis and development of the Albanian nation in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. The Bulgarian editing house Siela published her work in Bulgarian posthumously, and the German translation of this work under the title Der Einfluss Osterreich-Ungarns auf die Bildung der albanischen Nation 1896-1908 was also published in December 2013.

It should be noted that Teodora Toleva built her name in Bulgarian historiography by being a very industrious researcher, with high professional standards, an extraordinary polyglot (she spoke Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Russian, English and German). Besides this she was noticed back in 2006 for her capital work Foreign Policy of Gyala Andrássy and the Macedonian Issue, and posthumous publishing of her third book Genocide and the Fate of the Armenians 1905 is soon expected. We are emphasizing all this for comprehending that this work of hers, defended in Spain, is a work valuable of attention of the Serbian historians as well, who not rarely shy away from studying Bulgarian historiographical works.

Toleva concluded “After thorough studying of the archives we may claim that at the beginning of the 20th Century the Albanian population did not still represent a formed nation. The ethnical groups in Albania live isolated; they do not have connections between themselves, except when fighting. The possibilities for their convergence were practically nonexistent; murders are common, even for the people from the same clan. There were two basic dialects in the country that were so different that people could hardly understand each other. There was no unique literary language, but more than twenty different manners of writing in local dialects. The coefficient of literacy did not even exceed 2%. The population belonged to three religious confessions – Muslims, Orthodox and Catholics. The Albanians did not have national awareness, they did not have general interests, they did not express solidarity and they did not develop in the direction of waking the national feeling. Hence, at the beginning of the 20th Century there wass no Albanian nation.” Тoleva considered that her material evidence proved that Austro-Hungary was the most responsible for the creation of the Albanian nation, having 1908 as the crucial year, after which better times came for forming the Albanian nation.

It is interesting to see what reputed intellectuals from the West think about this work.

The Catalonian professor Ph D Agusti Colomines i Companys from the University of Barcelona said: “In her work Toleva comes to the conclusion that the Austro-Hungarian diplomacy played a crucial role in developing the feeling of national belonging of the Albanians in the Ottoman Empire, which had transformed into a dungeon of nations in the same manner as Austro-Hungary did itself. The political activity of Vienna was crucial in the process of national building in the light of Ernest Gellner and his modernistic theory, which later led to constructing the Albanian state”.

Comment

-

-

Additional connection(s) between modern Albanians (namely Labs or Liapides) and Mardaites: the modern Kurvelies or Labs were also designated by the Byzantines under the name of the Mardaites.

Documents inédits relatifs à l'histoire de la Grèce au Moyen âge publiés ..., by Konstantinos N. Sathas.

Page PREFACE XV, footnote 1:

"Parmi les Albanais persistent encore les noms Cabires et Mardaites, les Chanoniens ou Liap se disant encore Kurvelies, et les montagnards de Scodra, Mirdites. Comme nous verrons, les Kurvelies modernes etaient aussi designee par les Byzantins sous les nom des Mardaites."

Which translates to:

"Among the Albanians still persist the names Cabires and Mardaites, the Chaonians or Liap still call themselves Kurvelies, and the mountaineers of Scodra, Mirdites. As we shall see, the modern Kurvelies were also designated by the Byzantines under the name of the Mardaites."

Labëria

Kurvelies=Kurvelesh

Last edited by Carlin; 04-17-2017, 11:38 PM.

Comment

-

-

Sir Arthur Evans

Antiquarian researches in Illyricum

Pg. 107:

"Amongst the Albanian tribes the evidence of the absorption of Romanized elements is still more striking, nor is this anywhere more evident than amongst those members of the Albanian race who inhabit the Dardanian ranges."

Comment

-

-

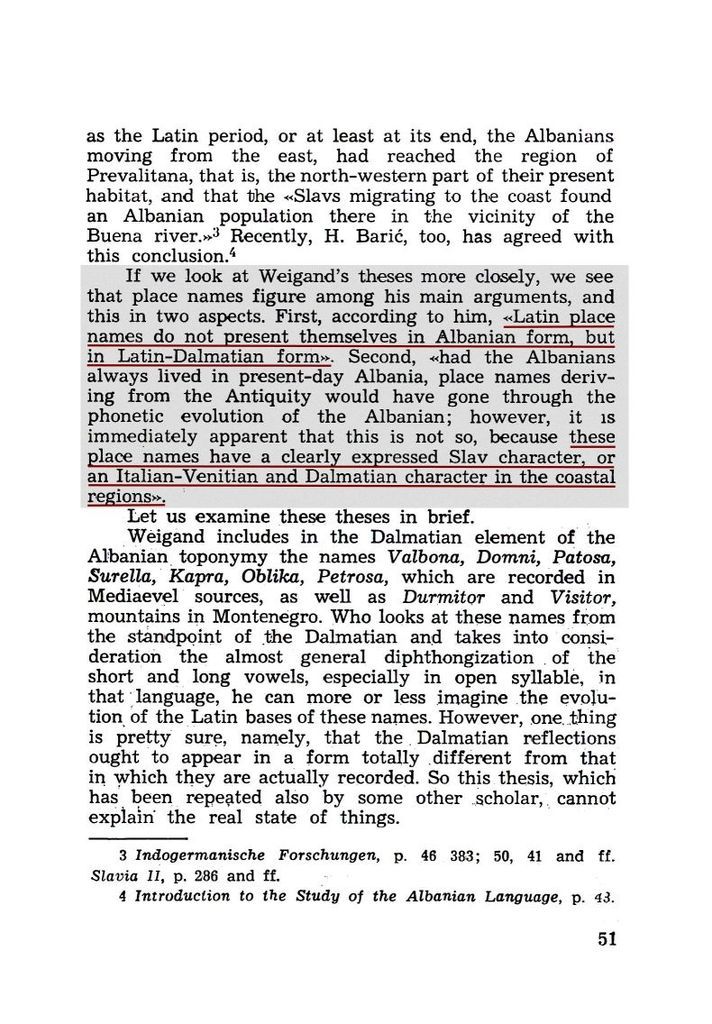

Eqrem Cabej page 51 -

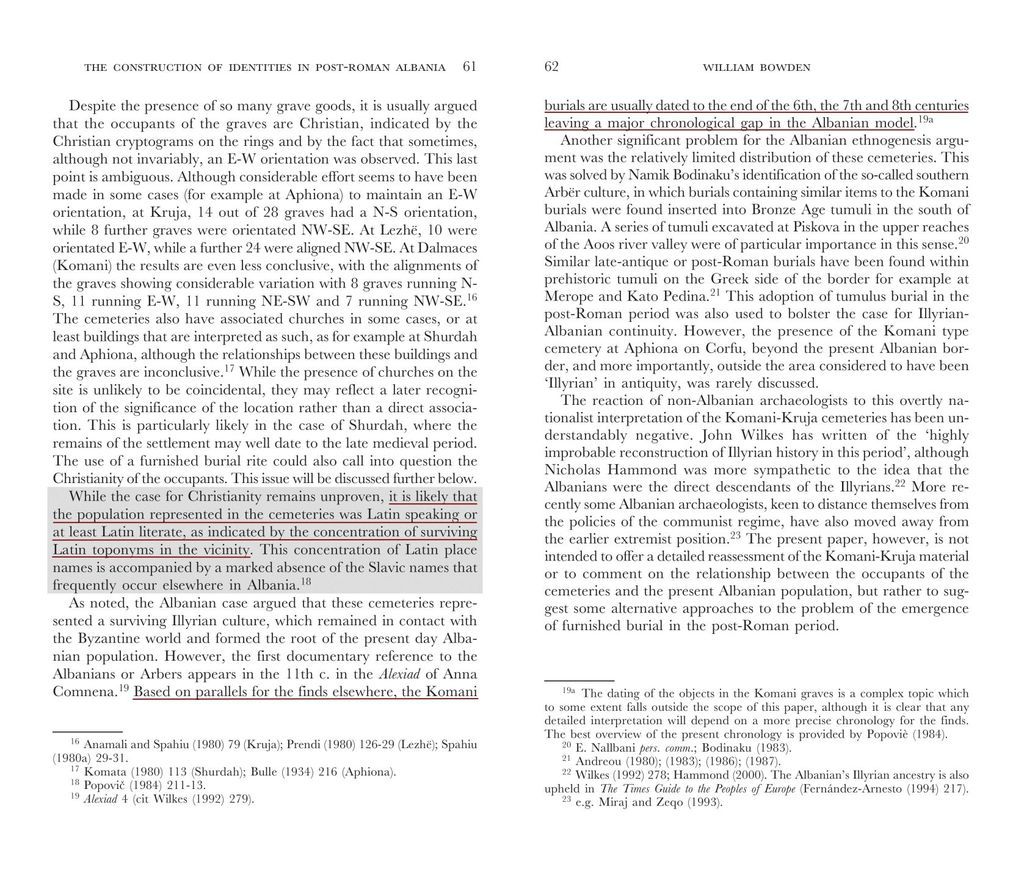

In the text of the picture, Eqrem Cabej refers to the positions of Gustav Weigand, who was the first to question, with serious arguments, the case of the origins of Skipetars from the ancient Illyrians. G. Weigand's arguments were mainly two, mainly linguistic.

G. Weigand's first argument concerns the "form" of the toponyms of Albania which do not have Albanian "form" but Latin-Dalmatian. The second argument concerns the fact that if the Albanians always lived in the area of present-day Albania, the ancient place names of the region would have evolved on the basis of the vocabulary of their own language, which is not the case. It is immediately evident, according to G. Weigand, that these place names have a clear Slavic "character" or an Italian-Venetian or Dalmatian character in the coastal areas.

What do these mean? Quite simply, the place names of Albania do not come from the Skipetarian language, but mainly from the Dalmatian language (a Romance language akin to Vlachika - but not the same).Last edited by Carlin; 04-30-2017, 08:47 AM.

Comment

-

Comment