Omg

.

The Macedonian Minority in Bulgaria

Collapse

X

-

Georgi Traykov Girovski from Vrbeni, Lerinsko

On April 23, 1964, he became head of state and chairman of the National Assembly of Bulgaria, following the death of Dimitar Ganev. He remained head of state until July 7, 1971 when the leader of the communist party, Todor Zhivkov, took that position. 1972–1974 Traykov was First Deputy Chairman of the State Council.

Leave a comment:

-

-

It continued longer than many realise. My grandmother's brother was a politician there. Anything good about Bulgaria was Macedonian and still is.

Leave a comment:

-

-

Kosta Šahov claims that the highest positions in Bulgaria were occupied by Macedonians:

Leave a comment:

-

-

Yes! In the process of photocopying parts of the book I found particulary interesting. I have uploaded some other images to other threads already.Originally posted by Carlin15 View PostThanks. Do you have any additional pages?

Leave a comment:

-

-

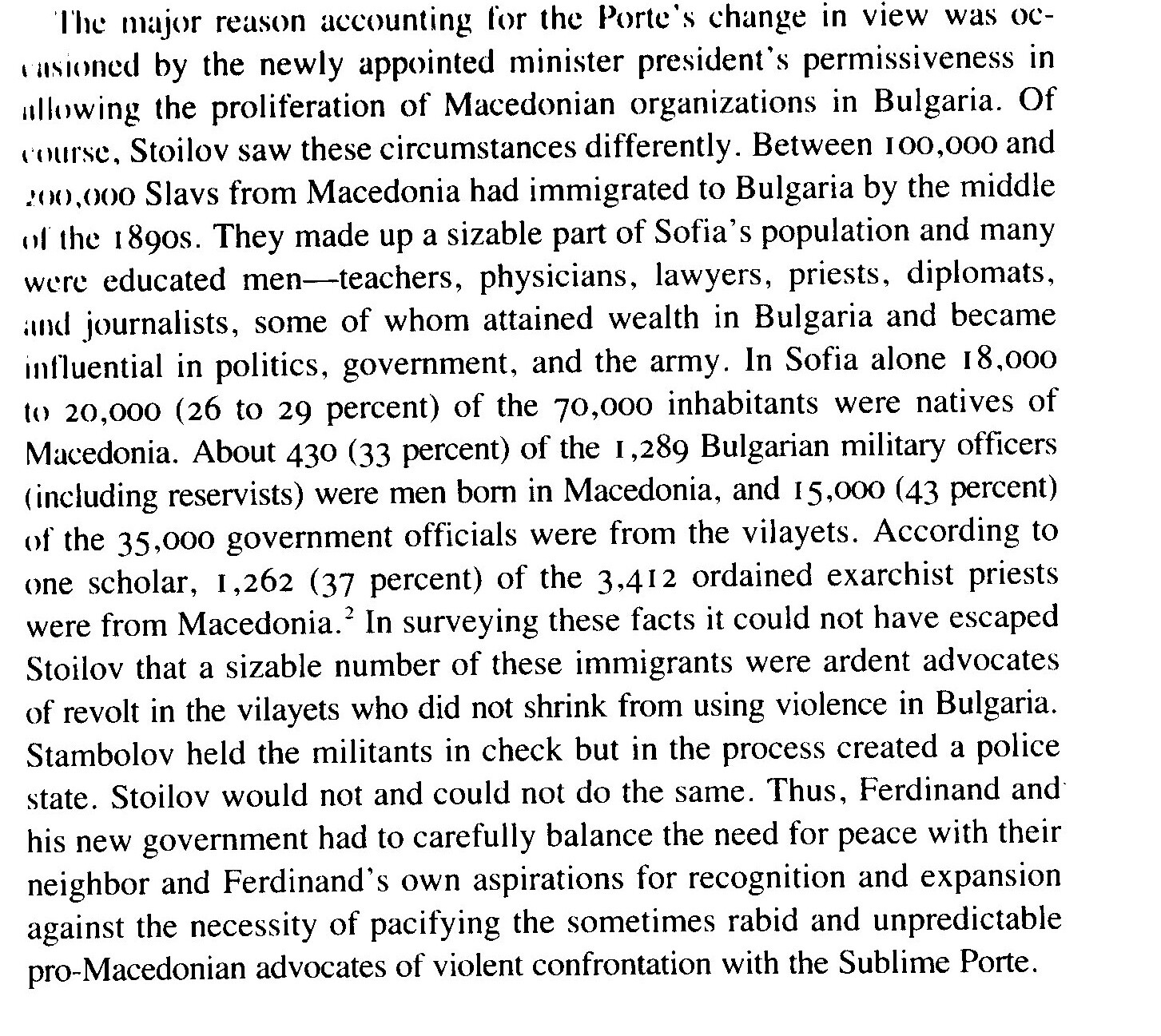

The Macedonian minority in Bulgaria in the late 19th century. From Duncan Perry's The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Revolutionary Movements, 1893-1903.

Leave a comment:

-

-

In the Ghetto. The Roma of Stolipinovo (Full Documentary)

URL:

"In the Ghetto. The Roma of Stolipinovo” documents the perspectives and experiences of Roma inhabitants in their neighbourhood over the last decades. It tells a striking tale of unemployment, hunger, insufficient medical care, illiteracy and segregated schools in one of the biggest Roma ghettos in Southeastern Europe.

The documentary shows Stolipinovo in the years before and after the accession of Bulgaria to the European Union (2006/2007) and illustrates the extreme living conditions and their relation to perpetuated persecution and discrimination, which are unfortunately still relevant today.

Hermann Peseckas and Andreas Kunz were the first film makers to shoot a feature-length documentary in Stolipinovo and they give an inside view on traditions, history and everyday life "In the Ghetto".

Direction: Hermann Peseckas

Script: Andreas Kunz, Hermann Peseckas

Music: Petar Vaklinov

Editing: Hermann Peseckas

Sound: Andreas Kunz

Camera: Hermann Peseckas

Production: Studio West

Release Date: 2009

Technical Data: DV Cam, 75 min

Language: Bulgarian with Engl. Subtitles

Leave a comment:

-

-

This post is a shocker..

The TFR of Macedonia is 1.5, the Muslim TFR would be 1.7 where the Macedonians is 1.3 amongst the lowest in the world. You dont have to be a mathematician to figure out the sum results if the status quoontinues.

Dont worry about Bulgaria..

Leave a comment:

-

-

Huns, Tartars, Khazars, Asian, Turko-Mongoloid.

Is there any information that details whether the Bulgar’s were a distinct ethnic group and not a mixture of peoples “prior” to fleeing into Eastern Europe?

Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1968.

Bulgaria, II. History

The Bulgars. - The first mention of the Bulgars in European history occurs towards the end of the 5th century A.D, the name being applied to some of the numerous tribes of non-Indo-European origin that had followed in the wake of Attila’s invasion and settled down temporarily in the steppes north of the Black sea and to the northeast of the Danube. These tribes of fierce, barbarous horsemen, despotically ruled by their khans (chiefs) and boyars or bolyars (nobles), lived mainly from war and raiding. Little is known about their religion. In A.D. 433 their federation of tribes spilt into two main groups-the Utiguri to the east and the Kutuguri to the west. About 560 the Avars conquered the Kutiguri and assimilated the survivors, so that the Kutiguri then disappeared from history. Less than a decade later the Utiguri were enslaved by the Turks.

The next name to appear is that of the khan Kubrat, ruler of a tribal confederation north of the Black sea that lasted until the middle of the 7th century. One of the Kubrat’s sons, Asparukh or Isperikh, moved westward under the impact of the advance of the Khazars (q.v.), crossed the Danube in 679 and settled down in Moesia, which was then a province of Byzantine empire. In 681 the Bulgar state in Moesia was officially recognized by the Byzantine emperor Constantine IV. Asparukh’s horde, probably not very numerous, was gradually assimilated by the more advanced Slavs, whos language and ways of life the Bulgars adopted.

Atlas of world history, volume one. 1978.

Hermann Kinder and Werner Hilgemann

The Bulgars: remnants of the Huns retreated into the steppes of Southern Russia, where, mixing with the Ugrians, they established a Bulgarian state, which reached its greatest power under Kuvrat (d. 679). After the destruction of this state by the Khazars. One group established a Danube-Bulgarian state, and another a Volga-Bulgarian state, which were eliminated by the Mongols (13th century); the remainder subjected themselves to Khazar rule.

Leave a comment:

-

-

This is from an article titled, 'The Bulgarians', in the July 1980 issue of the National Geographic by Boyd Gibbons. His case study is the Tunov family of Gorna Sushitsa in Pirin Macedonia. The article itself is an interesting read but what caught my eye, in particular, is the author's following account on page 100:

After dinner Vangalia dialed the radio until she found some folk music broadcast from Skopje, the capital of the Macedonian republic in Yugoslavia. Because of their Macedonian heritage, Bulgarians in the Pirin listen regularly to Macedonian folk music from Yugoslavia.

What is often referred to on the Balkan Peninsular as the "Macedonian question" is not a question at all. It is a century of failures by Bulgaria - in the Balkan Wars, and again in both World Wars allied with Germany - to regain all of Macedonia and territories south to the Aegean, where Bulgarian shepherds once wintered their flocks.

Bulgarians say that the people in Macedonia are Bulgarian. That sends the Yugoslavs into near apoplexy. The Yugoslavs assert that Macedonians are Macedonians, and that Georgi Dimitrov as much as said so. In recent years the Bulgarian census showed few Bulgarians in the Pirin being counted as Macedonians. It might help explain the Kalashnikov submachine guns bristling on their tense frontier to recall that the Yugoslavs didn't call this simply a case of census manipulation - they branded it "statistical genocide."...Earlier I had asked Atanas whether he considered himself Macedonian or Bulgarian. "I am Bulgarian."

Judging by the author's earlier observations about the "Kalashnikov submachine guns" being the reason for the sudden change of heart by the inhabitants of the Pirin region to go from Macedonians to Bulgarians, I doubt the author was convinced by Atanas' reply.

Leave a comment:

-

-

Thank you for posting that extensive reference Amphipolis. I trust you read it too and decided that the article speaks for itself and that no further commentary is needed? I can summarise it in one sentence for you if you like. All Draganov is saying is that the various Macedonian dialects that the Bulgarians and Serbs are trying to pass off as the purest form of Bulgarian and Serbian is in fact neither but simply Macedonian.

Leave a comment:

-

-

Petar Danilovich Draganov[1],

1888:A New Work on the Ethnography of the Macedonian Slavs

Even today the collection of the Miladinov brothers, which has long since become a bibliographical rarity, serves as almost the only source of information for the ethnographic and dialectologicad study of the Slav section of Macedonia, a land of varied peoples, languages and cultures. However, while there are valuable examples in the Miladinov'a book -- printed in the original Greek transcription -- they are only from the regions of Struga, Kostur (Kastoria), Debar, Ohrid, Veles (Koprulu), Bitola (Monastir), Prilep and Kukush (Kilkis).

This is a relatively small number of places when we take into consideration the fact that, according to the data of the Bulgarian, A. Ofeikoff (a pseudonym), there are 3,289 places in today's Macedonia. And for the insignificant collection of S.I. Verkovich (Narodne pesme makedonskih Bugara - Folk Songs of the Macedonian Bulgarians), we find in it new examples for only (the village of) Krushevo (Mrvachko)[2], the Razlog region, and primarily the Serres region. In 1885, there appeared the first part of an anthology conceived as a comprehensive work by K. Shapkarev from Ohrid; in it there are excellent examples of little-known Macedonian prose, but again, they are not of significant interest for the study of the Macedonian dialects, because they come from the aforementioned regions of Ohrid, Prilep, Kukush, with the addition of the region of Gevgelija.

Information about the Debar subdialect has been substantially enriched by I.S. Jastrebov with the publication of his collection of songs and customs of the Serbs from the Kosovo vilayet. Prior to Mr Jastrebov's work, two or three examples from that area were published by M.S. Drinov (in Periodichesko spisanie -Periodic Journal in Braila). This, however, is not adequate. To which branch should this Debar subdialect be linked -- to the Serbian or the Bulgarian -- or is there no need to link it to either of them? The poorly edited, often inaccurate examples in the biased collections of M. Milojevich (Pesme i Obichaji Ukupnog Naroda Sprskoh -- Songs and Customs of the Whole Serbian People) and S. Verkovich (Slav Vedas), certainly cannot be taken as reliable sources. A. Dozon's collection is no better, although this collector, being a foreigner, can be forgiven his errors. This seems the place to say that the late Bulgarian critic and writer, Luben Karavelov, in his book Znanie (Knowledge) (1876), was correct in his sharp judgement of these Macedonian forgers -- both Bulgarophiles and Serbophiles (Verkovich, Dozon, Vezenkovich, Milojevich and others). Finally, to this we should perhaps add the numerous and useful ethnographic notes and examples of the so-called Macedonian dialect, scattered throughout a multitude of Bulgarian periodicals published at various times and in various cities of South-Eastern Europe and even in the Middle East. Not a third of this number of journals is to be found in the Sofia or Plovdiv National Libraries. And a Slavist could find even fewer of these editions in his study room. He would have to dig through newspaper morgues in order to find two or three details of interest to him. So we see that in spite of all our persistent studies, we managed to find very few, and then not always satisfactorily edited, examples. And these are solely from the following dialects:

the Salonica dialect -- in the Constantinople journal Sovqtnik (Advisor) of 1865 (reprinted by M. Gattalo in V. Jagich's Knjizevnik (Writer);

the Voden dialect -- primarily one song, which was accidentally included in the Miladinov's collection, and one other, poorly edited by M. Milojevich;

Kratovo dialect -- of which there is a very good monograph in Braila Periodichesko spisanie;

Dzhumaja dialect -- in the Western-Bulgarian (Shopic) Collection of V. Kachanovski;

Melnik dialect -- one song, from the same collection;

Shtip dialect -- two songs, poorly edited in Plovdiv Nauka (Science)

Tetovo dialect - one song honoring King Lazar, which we find with I. S. Jastrebov (it is also given by M. Milojevich, but it is either printed with errors or incorrectly written down);

Nevrokop, and

Ahachelebisko dialects[3] -- unphonetic songs, published in V. Cholakov's collection.

In addition there is the South Pomak dialect: in Bulgarian Iljustracija (Illustration) of 1882, by H. Konstantinov; in N. Shishkov's collection of 1886 (Plovdiv); by P. Slaveikov, Nauka 1882/83; by the Russian ethnographist, A. A. Bashmakow, also published in Nauka and finally by the Czech Bulgarist, K. Irechek, in book 8 of Periodichesko spisanie. Considering all of these, we have at our disposal material primarily from the part of Macedonia which borders on Albania.

We have a few accidentally and consequently not always well edited examples of some dialects spoken on the left side of the River Vardar. We have no examples whatsoever from South-Western, South-Eastern, and most important, Northern Macedonia. The latter represents a bone of contention between the Serbian and Bulgarian patriots, and even between some philologists. That is, we have not a line of specially published dialectological and ethnographical material from the following regions: Salonica, Enidzhe-Vardar, Doiran (Polin), Voden (Edhessa), Meglen, Kichevo, Resen, Lerin (Florina), Petrich, Drama, and regrettably not from Skopje, Kumanovo, Kriva Palanka, Kochani and Gostivar. Now if one does not want to believe the honest word of the Bulgrarians or the Serbs, who persistently claim that the whole Slav population of modern Macedonia speaks the dearest, one and inseparable literary Bulgarian, or respectively, literary Serbian language, one must state that it is necessary to investigate and prove such claims. In spite of the fact that the Macedonian Collection (Collection Macedonienne) is being published by the Bulgarian Exarchate and edited by Mr Ofeikoff with clear propagandist aims, i.e. to defend the Greater-Bulgarian idea of Macedonia from the corresponding Serbian idea, it will contribute a great deal to the treasury of Macedonistics.

According to the now available data, this collection will comprise 1,500 examples from all the regions of the Macedonian Slav province, recorded by Macedonians themselves and sent to the Bulgarian Exarchate by its activists and teachers in Macedonia. The title of the collection has also been aptly chosen: they do not use the Bulgarian but the neutral Macedonian Slav name (Macedoine Slave). This demonstrates the aim of the collection to be objective in the future study of the philological issue, thereby once and for all deciding whose examples these are - Serbian or Bulgarian. Do they belong to the aspirants partially or entirely? Are there some examples that should belong neither to the Serbs nor Bulgarians, but entirely to the Macedonians? It is regrettable that this eagerly awaited collection (and its texts) have not yet been seen by the world, with the exception of the article mentioned above, by the Bulgarian scholar, Mr Ofeikoff, representing profession de foi (a confession, editor's note) of the Great Bulgarian idea, and Mr. A. P. Sirku's article on Macedonian philology, which comprise the first part.

The historical articles of professor M. S. Drinov and Mr V. V. Kachanovski should appear later. Articles of the well-known historian of Bulgaria, K. Irechek, and two other Slavists should have been included in the collection, however they refused to participate. It has become imperative that these articles, written partly in Bulgarian and partly in Russian, should be translated into French, since their special purpose was to present them to the Western European education experts. And above all, the translation is necessary to reach the political and diplomatic circles who, the publishers hope, will identify themselves with the collection's central idea, in the practical resolvement of the Macedonian Question. Concerning this, we must note here that the diplomats, accustomed as they are to the preciseness of the French language, its exactness and clarity of expression, will be probably horrified by the French into which these articles have been translated. They may also be hororified by the printing and grammatical errors in the French introduction and especially in Ofeikoff's article. It is obvious that Mr Ofeikoff's lengthy introduction is an adaptation of his article which appeared last year in that mouthpiece of the future European Afghanistan and that of the future close "confederation" of all the Peoples of the Balkan under the protection of Austria, Revue de l'Orient. The latter is published in Budapest by the Hebrew, W. Weltner, the Pole, DePulski, and the Hungarian, Attila Semera. The Revue maintains a permanent staff of investigators and correspondents at large -- Bulgarian, Serbian, Wallachian (Romanian) Macedonian, Greek, even Turkish -- who are allowed to freely indulge in the scholarly polemics of the Macedonian subject.

Ofeikoff"s article is nothing but an elaborate polemic with the prominent Serbian writer, Matija Ban. Mr Ban has continued up to present day to dispute his Bulgarian opponents on the subject of whether the Ohrid Exarchate (i.e. Archbishopric, editor's note), the former Prima Justiniana, the centres of which were Skopje and Kustendil, was Bulgarian or Serbian church. Mr Ofeikoff quotes Ubicini, I.Miiller, Grisebach, Kolb, Bart, Hilferding, N. N. Obruchev, Mackenzie, Irby and others, who have allegedly long ago on an academic level resolved the Macedonian language question in favor of the Bulgarian patriots, and draws the conclusion that "all those well-known authors, ethnographers and travelling writers bear witness to the fact that Macedonia is populated by Bulgarians only" (Cf. Revue de I'Orient, 1887, No. 27). He also claims this in his new work, the only difference being that the latter is even more embellished with vain assumptions. For example, Mr Ofeikoff here mentions the following authors: Y. Venelin, P. J. Safarik, I. Muller, V. I. Grigorovich, Ami Boue, Cruz, Grisebach, Peterman, A. F. Hilferding, Lejean, Dumas, Dozon, Stein, Kolb, Reklyu, Bush, A. S. Budilovich, N. S. Obruchev, and A. F. Ritih, V. S. Teplov, V. V. Kachanovski, Mackenzie, Irby, Lavelle, plus such historians as Paisii Samokovski (the author of Tsarstvenik (Lives of Kings) and L. Dobrov (the author of Turki i Slavjane (Turks and Slavs)), and derives this conclusion: "None of these scholars has traveled through European Turkey aiming to reveal the Bulgarians. All of these writers and ethnographers declare that Macedonia is populated with Bulgarian Slavs"(p. 7).

But such a dogmatic solution to the Macedonian Question does not correspond by any means with the exceptionally complex scientific difficulties this question represents. As far as A. P. Sirku's article on Macedonian phonology is concerned, albeit unsystematic and verbose, it represents a complete exposition of all that has been shown up to now in the few published examples of Macedonian dialectology. The new thing here is that the author presents his own classification of the dialects in the Bulgarian language. He mentions four dialects: Thraco-Mysian, Shopic, Rhodopic or Rupalan (Rupis) and Macedonian. Another unique thing is that he writes in detail about the Rhodopic dialect partly from the material published by V. Cholakov, P. Slaveikov and N. Shishkov, as well as on the basis of S. Verkovich's Vedas. Furthermore, Sirku writes about the Debar dialect, disputing the well-known assertions of I. S. Jastrebov concerning this dialect. And he exhausts the scientific literature available on the nasalisms )|( and A in modern Macedonian Slav dialects, which are related to the East Bulgarians nasalisms. Doubtlessly he did not know that there is also nasalism or rineism in the Voden, Meglen, Resen and Demir Hisar dialects, and that the triple postpositive article in Macedonia is not only characteristic of the Rhodopic Pomaks, Tikvesh and Debar areas, but also of all the Brzaks (Brsyaks) from Prilep, Veles, Bitola and other regions. Therefore, it is understandable that Mr Sirku, starting from the known published literature on the Macedonian vernacular, has looked more extensively into the Rhodopic than the Macedonian dialect. However, the Western Rhodpic dialects on the border between Thrace and Macedonia are not so important to the academic solution of the Serbo- Bulgarian language issue, as are the dialects in South-Western, and especially, North-Western Macedonia. These apparently are completely unknown to Mr Sirku, so that what was unknown before remains so.

To expect others to believe from him what the Bulgarian experts themselves do not know is, to put it kindly, difficult. It is therefore with impatience that we await the publication of the Bulgarian Exarchate Macedonian Collection with its 1,500 examples of "folk songs, collected from peasants from all Slav Macedonia." Nor would it be inappropriate for the Serbian Academy of Sciences (the former Serbian Scientific Society), from its side, to edit and publish a Macedonian collection. Certainly, though, it should not be like the collections of M. Milojevich and Vuk Karadzhich, but compiled Sine studio et sine ira. Perhaps this is the place, too, to mention that currently the Serbs have their own consulates in Macedonia, lead by Mr S(tojan) Novakovich, a Serbian (diplomatic) delegate to Constantinople, who is also a respected philologist and has paid great service to Bulgarian literary history. In addition, if I succeed in publishing the Macedonian collection I have compiled, comprising about thousand texts from 105 populated areas in Macedonia, we can assume that with these combined materials the major problems of Macedonian dialectology can be solved. Having all this at our disposal, the Slav philological science should be able to solve, once and for all, the Macedonian language issue and to decide impartially what in these three Macedonian Slav collections belongs to the Bulgarian vernacular and what to the Serbian, and what then naturally, because it belongs neither to the Serbian nor Bulgarian, is the property only of the separate and independent Macedonian vernacular.

(Journal of the National Education Ministry), St Petersburg, Book CCLV, April 1888.

NOTES

[1] P. D. Draganov (1857-1928) was a versatile Russian Slavist of Bulgarian origin. He was graduated in 1884 from St Petersburg University, Faculty of History and Philology. He was granted the title of Candidate of historical and philological sciences at the same university. He was a professor in the Bulgarian Exarchate grammar-school in Salonica for three years (1885-1887). He wrote several works on Macedonistics. In this article he makes an analysis of A. Ofeikoff's work (a pseudonym for Atanas Shopov, secretary of the Bulgarian Exarch in Constantnople) entitled La Macedoine au point du vue ethnographique, historique et philologique Philopopoli, 1887.

[2] Krushevo is a place in the Demir Hisar district, Serres region (in Aegean Macedonia).

[3] Ahachelebisko is a place in Western Thrace.

Leave a comment:

-

Leave a comment: