Macedonian Societies in Switzerland & The Paris Peace Conference

Collapse

X

-

Macedonian Societies in Switzerland & The Paris Peace Conference

Ние македонците не сме ни срби, ни бугари, туку просто Македонци. Ние ги симпатизираме и едните и другите, кој ќе не ослободи, нему ќе му речеме благодарам, но србите и бугарите нека не забораваат дека Македонија е само за Македонците.

- Борис Сарафов, 2 септември 1902

-

What really happened at Paris; the story of the Peace conference, 1918-1919

Had the terms of the secret Treaty of London of 1915 been carried out, Albania would have been divided. The central portion would have been an autonomous Mohammedan state under Italian protection; the northern part would have been under the protection of Jugo-Slavia, and the southern part was to have been divided between Greece and Italy. Koritsa would have become a Greek city, Valona an Italian stronghold and point of penetration; Scutari and the Drin valley would have become an outlet for Jugo-Slavia’s trade....

-------------

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED AT PARIS

VII

CONSTANTINOPLE AND THE BALKANS 1

BY ISAIAH BOWMAN \

[....]

THE BALKAN COUNTRIES

From being an undernourished and undeveloped part of the Turkish Empire, with life demoralized or even degraded, with persecution rife and with society of a low order of development, the Balkan lands changed their character in the nineteenth century and were brought within the limits of the western European indus- trial realm. They became the transit lands for a part of the Oriental trade under that autonomy or semi- dependence which they had gained by several centuries of effort. Under the protection of general European treaties whose execution involved chiefly the welfare of western European powers, the Balkan states increased in population, developed cities of considerable size and commercial importance, and put their products into the current of world trade. Though principally of impor- tance as transit lands, the Balkans became important, also, because of their own economic resources and the increased purchasing power of their people.

Two broad groups of Slavic peoples had developed, the Jugo-Slavs and the Bulgarians. The former is composed of such diverse elements as the Serbs and the Slovenes, and the latter, originally Finno-Ugrian, as the ethnologist would say, and not Slavic, has been so thoroughly penetrated by Slavic peoples in successive migrations that it is now properly classed as a Slav state.

The South Slavs form one of two great fingers of Slavdom thrust westward into Central Europe, and it extends all along the Adriatic, enveloping the key cities of Fiume and Trieste.

The degree of unity of these two Slavic groups, Jugo-Slavs and Bulgarians, is quite different. The Bulgarians are chiefly a peasant people, with fairly uniform economic advantages and ethnic qualities. Four-fifths of Bulgarian exports consist of agricultural products, and three-fourths of the imports are manufactured wares.

While the large estate has long been a feature of land tenure in Rumania, Jugo-Slavia, and Greece, Bulgaria is pre-eminently the land of small peasant proprietors.

Three-fourths of her land is held in small farms not exceeding twenty hectares (fifty acres). Proprietors holding more than thirty hectares (seventy-five acres) hold only 14 per cent of the total area of cultivable land.

In contrast to the Bulgarians the Jugo-Slavs are composed of most diverse elements. The Slovenes, for ex ample, fought in the Austrian army and faced Italian divisions up to the end of the war. By the Pact of Corfu, signed in 1917, and the organization of a recog nized government at Agram after the November armis- tice, 1918, the kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was created, and the group of Slovenes incorporated with the Serbs and Croats to form a new Allied state. Thus, by a political phrase, Croats and Slovenes became allies of the Italians, whom they had just been fighting! This was one of the facts that was used against them again and again by the Italians to support their claim to a large part of the Jugo-Slav territory and its commercial outlets at the head of the Adriatic.

The degree of unity of the Jugo-Slav state is altogether problematical, and doubt as to its political stability was a source of grave weakness in its diplomacy. There has been a steady growth of the agrarian party which seeks such control and division of the land and such commer- cial arrangements as will be of greatest benefit to it.

Opposed to each other are two other political groups, the one seeking a strongly centralized government, the other a confederation which would leave the various states with a high degree of political and commercial autonomy.

Such a state finds it difficult to manage its domestic affairs, and is almost groping in the dark in attempting to negotiate with foreign powers.

Thus the war has completely changed the orientation of the Serbian state, a part of Jugo-Slavia. Its original thought at the opening of the first Balkan War was to unite only its immediate kinsmen with the main body, and to secure a window on the sea. Because Greek troops captured Saloniki from the Turks after a long siege in 1912 Serbia was deprived of an outlet on the Agean. Her eyes thereupon turned to the Adriatic, and here she has struggled with Italy for just two years with the object of controlling the eastern Adriatic littoral.

Realizing that she could not win on the programme of 1919, Jugo-Slavia took renewed interest in her eastern frontier, where she was able to make gains at Bulgaria’s expense. To understand the background of this action requires us to digress a moment for a view of the general situation and an earlier phase of the treaty-making process.

The boundary settlements of the Balkans were made on a principle quite different from that which governed the making of the German treaty. The signatures of Germany and Austria had been obtained and the ratification also to the treaties of Versailles and St.

Germainen-Laye. It was a foregone conclusion that Bulgaria would sign. Months before, in the case of Germany, there was no such assurance. It is perhaps worth while, therefore, to sketch an historic incident that bears, if only by contrast, on the Balkan question, and which involves one of the most dramatic moments of the peace conference.

The early days of the peace conference were filled with organization plans, with a multitude of questions of the first order respecting the management of a world still largely under military control, and with hearing the insistent claims of minor nationalities. It would have been a ruthless spirit that denied a hearing to Poles, Czecho-Slovaks, Greeks, to mention only the leading delegations of minor rank. Their representatives were not trained in the principles of effective speaking. When Dmowski related the claims of Poland, he began at eleven o’clock in the morning and in the fourteenth century, and could reach the year 1919 and the pressing problems of the moment only as late as four o’clock in the afternoon. Benes followed immediately with the counter-claims of Czecho-Slovakia, and, if I remember correctly, he began a century earlier and finished an hour later! Venizelos, a more practised hand, confined himself to one century of Greek history rather than to five, and was adroit enough to tell his story in instalments. To listen to these recitals of national claims, to organize field commissions to Berlin, Vienna, southern Russia, etc., for gathering political and economic data on the spot, to draft the projects for reparation, the League of Nations, etc., filled the first two months of the conference.

At last it was apparent to every one that the conference had to be speeded up. It had accomplished a vast amount of labor in a brief time, but the taking of evidence in the supreme council had to stop. This work was thereafter largely assigned to commissions who then reported to the supreme council. To facilitate one branch of the work, the territorial settlements, and to determine the new boundaries, Premier Clemenceau, Mr. Balfour, and Colonel House planned to meet at the French Foreign Office on February 19. On his way to the conference Clemenceau was shot. Mr. Balfour and Colonel House went ahead with the arrangements. On the forenoon of February 21 a group of British and American experts met, at the suggestion of Colonel House, in my office, room 446 of the Crillon Hotel. The British delegation included Sir William Tyrell, Headlam- Morley, Lieutenant-Colonel Cornwall, and others ; among the Americans were Haskins, Seymour, and Johnson.

When the session ended at four o’clock in the afternoon of that day, the boundaries of Germany were tentatively sketched and the way prepared for a conclusion of the matter in the various territorial commissions that worked out the details.

The first boundary report to be presented and then argued before the supreme council was that of the Polish territorial commission, fixing Germany’s eastern boun- dary. Jules Cambon read the report of the Polish com- mission. At last the time had come for settling the de- tails of a particular boundary. Up to this time every- thing had been preliminary the taking of evidence; now there was to be fixed a definite frontier. Moreover, it was recommended that Danzig be given to the Poles, and the report of the commission was unanimous on this point. Here was an old Hanseatic town, a modern com- mercial port, a focus of sea-borne trade of great future importance. Trade is the life of the British Empire.

It was an Englishman who wrote that shipping was to England like the hair of Samson, the secret of strength.

Would Lloyd George continue in the role of irresponsible and playful plenipotentiary, or would he recognize the stake at Danzig Danzig, behind which were textile mills, coal, and the petroleum of the Carpathian fore- lands? Suddenly Lloyd George changed from a state of bored indifference to one of aggressive participation.

From that moment forward Lloyd George never relaxed his interest or his control. Sitting forward in his chair, and speaking in an earnest voice, he proceeded to tear the report to pieces, and the argument he employed wiped the smiles from the faces and drove fear into the hearts of his listeners. “Gentlemen,” he said, “if we give Danzig to the Poles the Germans will not sign the treaty, and if they do not sign our work here is a failure.

I assure you that Germany will not sign such a treaty.” There ensued a silence that could be heard. Every one was shocked, alarmed, convinced. Lloyd George had in- troduced a bogey and it had worked. Thenceforth the motto of the British premier might have been: “I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me!”

When the report was resubmitted to the Polish com- mission the next morning, it was the British representa- tive himself who brought a typed answer to the asser- tions of his chief, Lloyd George. When on the same day the supplementary report was read, President Wil- son reviewed in a masterly fashion the two sides of the question, emphasizing what had been promised the Poles in Article XIII of his declaration of January 8, 1918, before a joint session of the Congress of the United States.

Thereupon, with his eyes fixed upon the trade prize of Danzig and his mind fortified with the historic prece- dents so skilfully supplied by Headlam-Morley, Lloyd George moved that the report be tentatively accepted as read, but that final decision on Germany’s boundaries be reserved until all the territorial reports had been considered. Directly thereafter the council of four was organized, where decisions could be reached without the bother of territorial experts, with whose facts, or any other kind of facts except purely political ones, Lloyd George had no patience whatever. The next we hear of the Danzig question Lloyd George and President Wilson have agreed to make it a free city.

With this solution I have no quarrel. It was even with a sense of relief that we heard that the matter had been thus settled. While I believe that Danzig should be a Polish port, I also realize that there are two very big sides to the question. To find out what had been agreed upon and to give the agreement substance, Head- lam-Morley and myself waited on the President, for, within the space of an hour, to two different members of his staff Lloyd George had given two quite different versions as to what had been agreed upon between him- self and the President, and a midnight meeting between the British experts and myself failed to untangle the matter. The President reported that it had been agreed to follow the ethnic principle in delimiting Danzig’s boundaries and to give the city^a “free” status. Spread- ing out various maps upon the floor of the President’s study, we examined the matter in some detail, and de- cided to avoid discussion as to the relative merits of the ethnic maps of the different delegations by submitting a small map prepared by Lloyd George’s advisers. There- upon Mr. Paton, of the British delegation, and I set to work upon a large-scale map prepared by the American Inquiry, which was used throughout the Polish negotia- tions as the authoritative map on ethnic matters. Be- tween four and six o’clock we traced the boundaries of Danzig as they stand in the treaty to-day. Transferring these boundaries to the British small-scale map for the benefit of Mr. Lloyd George they were presented to the council of four, and there passed without delay.

Six months thereafter, and against the protest of the American representative on the supreme council, Sir Reginald Tower was appointed high commissioner at Danzig. His stormy course there could have been pre- dicted with mathematical accuracy by any one inter- ested enough to see why Lloyd George labored for a free city on the shores of the Baltic, where British ship- ping and capital were to be rapidly increased, and why Sir Reginald was chosen on the basis of a record in South America quite unfavorably known to many American merchants. In this and in many other matters the British knew just what they wanted and how to get it. In training and experience they were second to no other delegation, and they worked with a sureness of touch that aroused the deepest admiration.

No ‘such fear as that which beset the minds of the leading statesmen with respect to the German treaty assailed them when Bulgaria came to sign. The ceremony of the signing was altogether extraordinary. In the old town hall at Neuilly stood files of soldiers, guards with fixed bayonets were stationed at the angles of the stairway, the cars of the different delegations swanked up to the entrance, the Allied leaders took their seats, and very powerful and formidable they appeared. It was a splendid array. In the background was a compact mass of onlookers from the various delegations, including a sprinkling of women. It was a scene, and they were there to see it. Several bound copies of the treaty lay on the table. One looked to see the doors thrown open and a file of Bulgarian’ officials and a little ceremoniousness and, in short, something befitting the power and majesty of the sovereign Bulgarian people on a solemn and historic occasion. Instead, there was a military order in French in the hallway outside, the doors slowly opened, a half-dozen French foreign office secretaries rose and stood about the entrance, and after a pause a single gray-faced and very scared-looking, slightly stooped man walked slowly in and was ushered to a seat at one end of the room. Was all this ceremony and this imposing array for the purpose of dealing with this lone individual the peasant, Stambouliski?

It looked as if the office boy had been called in for a conference with the board of directors. Of course he would sign, as presently he did, very courteously escorted and supported by the hovering foreign office secretaries; and then the great chiefs of the Allies signed, and presently the lone Bulgar, still scared and wall-eyed, was led to the door, and thus furtively he escaped. The break-up of the rest of the assemblage wore the cheerful aspect of an afternoon tea. The Allies were at peace with Bulgaria!

What did the treaty do? It took things from Bulgaria. Were any of these actively protested? On what principle? These are important matters over which we would do well to reflect for a moment, for both during the war and the peace conference the position of the American Government was little understood, abroad as at home. On the one hand, we were accused of softness respecting a treacherous enemy state, an ally of Germany; and, on the other, we were thought heartless and lacking moral courage for signing a treaty that stripped Bulgaria of territory and property when we had never declared war against her. Let us see where the line of justice lies and exactly what was the record of the American delegation.

The Allies naturally viewed the peace now from the standpoint of imposing terms upon an enemy, again from the standpoint of abstract justice as expressed in President Wilson’s Fourteen Points. In the settlements now one view, now another was dominant. Thus the path of conciliation was everywhere made difficult. At every turn one must needs give documentary evidence of hating the enemy or one might be thought pro-German.

This state of things suggests a bit of self-analysis on the part of the man who didn’t like olives: “I don’t like olives, and I’m glad I don’t like ‘em, for if I liked ‘em I’d eat ‘em, and I hate ‘em.”

America’s chief representative was always powerful and respected, and on every occasion demanding clearness and vision it was he who stood head and shoulders above his associates. When I suggested to some of my British colleagues after a debate between Lloyd George and the President that we should keep score on our chiefs to see which made the most points, the reply was made: “Up to now, at least, your chief has won them all!”

But with delay in the Senate the influence of the American representatives grew steadily less. On one occasion Mr. Polk commissioned me to secure the opinion of Premier Clemenceau on the Fiume question, which was then leading up to one of its most critical phases.

It was late in 1919, we had not ratified the Treaty of Versailles, the conference was nearing its end, the American delegation was soon to leave. Tardieu reported his chiefs answer to our suggestion: “The Americans are charming but they are far away; when you have gone the Italians remain and as our neighbors.” Just at the end the power represented by America had a sudden burst of recognition. You will not find it in the minutes of the proceedings. The incident is historic. The German representatives were reluctant to sign the protocol of the final proceedings respecting the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles. The American delegation was to sail on December 5. At the close of the session on December 3 Clemenceau turned to Mr. Polk and begged him to postpone the departure of the American delegation. On his face were no longer the aggressive and determined lines of the victorious leader. There was a day when he had called the President pro-German and left the council of four in anger. Now he sought companionship as he walked through the dark pathway of his fears. Unless ratifications were exchanged all might be lost. “Mr. Polk, I beg you to remain. If you don’t the Germans will not sign. I beg you to stay. I beg you not to go.” The American delegation delayed its departure.

For the lopping off of this projection of Bulgaria into Macedonia puts an end, at least for the present, to the long process begun in 1870, with the foundation of the Bulgarian exarchate, and enhanced in 1878 with the autonomy of Bulgaria, which had for its object the Bulgarization of Macedonia and its ultimate annexation to the Bulgarian realm. This act and the tacit confirmation by the powers of the Serbo-Greek boundary in Macedonia throws the Macedonian question into its latest, possibly its last, phase. The refined ethnographic and linguistic studies of the past few years have shown contradictory or indefinite results as to the individualistic character of the Macedonian region. On the physical side it is made up of bits of several adjacent natural regions. On the religious side it might, in the nascent state in which it was in 1870, have just as readily become an appanage of Serbia as of Bulgaria. By 1912, however, over 1,100 Bulgarian churches had been established in the region.From the attitude of the American delegation in the case of the Adriatic dispute, it will be obvious what their position was in the case of those three salients of Bulgarian territory toward the west which Serbia coveted and eventually obtained by the Treaty of Neuilly, between Bulgaria and the Allied and Associated Powers.

These three salients are occupied by Bulgarian populations, and not only in the territorial commissions but also in the supreme council the American representatives opposed to the end, and had their opposition entered in the record, the giving of Bulgarian territory to a greatly enlarged Jugo-Slavia. That state already included Slovenes of doubtful allegiance, colonies of Germans and Hungarians north of the Save, Montenegrins and Macedonian Slavs who certainly wanted least of all to be added to Serbia. And now the Jugo-Slavs were bent, for strategic reasons the protection of the railway line from Nish to Saloniki on lopping off four pieces of Bulgarian territory and carrying the boundary in one place within artillery range of Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria.

Of the four pieces of territory which Bulgaria has lost on the west Timok, Tsaribrod, Bosilegrad, and Strumitsa the southernmost one, the Strumitsa salient, represents the most significant loss, and it is also the largest.

The population of Macedonia is estimated variously between 1,200,000 and 2,000,000, owing to the indiffer- ent boundaries of the region. More than half the people are Christians, and the rest chiefly Mohammedans, with some Jews. Each of the three adjacent states, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece, made an effort to impose its culture upon the people and to develop a nationalist sentiment among them. Though the Bulgarians at one time had possession of the region and though the racial character of the people is perhaps somewhat more closely similar to Bulgaria than to Serbia, the Serbs also held the country for a time and they left a deep impression there, as is shown by the architecture and the literature.

Greek influence was strong in Macedonia, because her agents operated chiefly in the towns, and these dominated large expanses of tributary country. Even Rumania joined in the effort to penetrate Macedonia; there are probably between 75,000 and 100,000 pastoral Vlachs of Rumanian affiliation in the whole Macedonian country.

But greater success was bound to attend the Bulgarian penetration, because from the first the Bulgarian religious organization had a nationalistic cast. It was intimately associated with the Bulgarian effort to achieve independence and to round out the Bulgarian realm so as to include all Bulgarian populations adjacent to the central group. Thus it sought to include lands in Turkish hands in eastern and western Thrace. It had as one of its objects the incorporation of Macedonia into Bulgaria and the recovery of territory inhabited by Bulgarians in the Dobrudja. When its religious teachers went into Macedonia they took with them not merely the faith of their church but the hope of freedom from the Turk, the pride of nationality which the Bulgarians had, and kinship with a closely related ethnic group. Naturally, under these conditions Bulgaria, at the close of the first Balkan War, looked upon Macedonia as her own, and the restriction of approach of Serbia to Saloniki on the south was acknowledged by the Serbians themselves. In the secret treaty with Bulgaria just before the first Balkan War, Serbia agreed to the definition of a neutral strip running east-northeast to Lake Okhrida, one hundred miles northwest of Saloniki, which was to be the subject of later negotiation between her and Bulgaria. The later negotiation never took place, for Bulgaria made unexpected gains in eastern Thrace, and the powers decided to form an independent Albania in the regions where Serbia had hoped to increase her territory. Serbia and Greece denounced the territorial terms of the alliance, Bulgaria insisted on them in spite of changed conditions, and the second Balkan War resulted. With the complete success of Serbia and Greece, as opposed to Bulgaria, they divided Macedonia between them, leaving only the Strumitsa salient and the country immediately northeast and east of it to Bulgaria; and the Treaty of Neuilly, by taking away the Strumitsa salient has shut the door on Bulgaria’s expansion in this direction.

The Macedonian question, once the chief political problem of the Near East, has passed into an entirely new phase. Neither Greece nor Serbia is expected to give up Macedonian territory for a possible future Macedonia.

The Macedonians are without leaders of real ability, and the heterogeneous character of the population makes it impossible for them to have, or to express, a common public opinion. There are no significant resources. It is a poor country, unwooded, rather desolate, and will always be commercially tributary to communities or states that are richer and economically better balanced.

It is therefore improbable that the Macedonian question will be revived except through the possible cruelties of Greeks and Serbs in their treatment of the Macedonians.

It was a part of the programme of the American delegation that, while the Strumitsa salient should properly be removed because of the menace which it carried to Greek and Serbian railway interests from Nish to Saloniki, Bulgaria should not suffer the loss of the two middle bits of territory Tsaribrod and Bosilegrad. For Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, is brought within thirty miles of the new frontier, that is, within the range of modern gunfire; and there is no warrant at all in ethnic considerations for a change from the frontier as it stood before the beginning of the war. But the government of the kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes desired to rectify their frontier. Not at all sure of a satisfactory settlement of the Adriatic question, Jugo-Slavia sought to make the best of the new boundary arrangements elsewhere. With Greece, a friendly ally, on the south, she could hope for no expansion of her national domain toward Saloniki, and it was altogether doubtful if she could obtain compensation in northern Albania, as had been promised by the secret Treaty of London in 1915.

But two other places remained where advantages could be secured : on the north, where the enemy states of Austria and Hungary were to have their frontiers defined; and on the east, where the Bulgarian frontier was yet to be established. It was not in the interests of justice, it was solely in the interest of the Jugo-Slav state, that Bulgaria suffered territorial losses on the west. The American delegation protested, both in the territorial commissions and finally before the supreme council, against these losses of territory, claiming them to be unjustifiable according to any principle that had governed the peace conference theretofore, and emphasizing the menace of war that they invited.

While the arguments of the American representatives were courteously received, our delay in ratifying the treaty had weakened American prestige. If the loss of territory pained an enemy, Bulgaria, it pleased an ally, Jugo-Slavia.

Germany and Austria had signed; Bulgaria would also sign. The territory could be taken with impunity. Politics had become quite practical; the Fourteen Points and their exponent, as Clemenceau had said, were far away.

However charming the Americans might be, the Jugo- Slavs were nearer, and there remained the Adriatic dispute to settle. Perhaps a concession on the east would soften the blow that impended on the west. When Jugoslavia insisted on taking land from Bulgaria by the Treaty of Neuilly, she paved the way for

The territorial losses of Bulgaria appear slight, but the political stability of the state has been seriously affected by them. By tacit confirmation of the northeastern boundary of Bulgaria in the Dobrudja, on the part of the powers, Rumanian merchants of Braila and Galatz are given a vital hold upon that one-fourth of Bulgaria’s foreign trade that passes by way of the Danube. She is deprived of an outlet on the Aegean save by the untried experiment of international guarantee of transit trade across a neighboring state, and the possible internationalization of the Maritsa River, as provided in the still unratified Treaty of Sevres. Under these circumstances her primitive economic organization lends itself the more readily to exploitation by foreign capital. More than a fifth of so called Bulgarians live outside her new national boundaries 200,000 in Thrace, 200,000 in the Dobrudja, 800,000 exarchists in Macedonia or a total of 1,200,000.On the other hand, we must remember:

(1) That in September, 1915, Bulgaria agreed to join Austria-Hungary against Serbia and in return was to receive a certain share of Serbian land and people.

(2) That Bulgarian authorities at one time even declared that Serbia no longer existed and had become Bulgarian, closed schools and churches, and even burned them, compelled the people to speak Bulgarian, and, like the Germans in Belgium and northeastern France, levied fines and contributions, took away food, and ruined the country.

(3) That out of tens of thousands of Serbians interned in Bulgarian camps, at least half died.

(4) That Bulgarian outrages upon Greeks and Serbs men, women, and children were among the most hideous of the war.

Favorable to national solidarity and political control is the compact layout of the land. Favorable also in this respect is the ethnic purity of the people. Of 4,000,000 population, 80 per cent are Bulgarian (as contrasted with 60 per cent of Czecho-Slovaks in Czecho-slovakia). Turks are found chiefly in the east and Greeks in the towns.

Perhaps the principal focus of territorial difficulty in the Balkans is Thrace, whose eastern and western sections affect the commercial outlets of Bulgaria in a critical way. This whole territory was coveted by Greece and claimed on ground of strategy, ethnography, and commercial advantage. A secret treaty, signed in February, 1913, approved of the cession of Kavala to Bulgaria on the ground that it was the natural outlet for the western section of that country, and at that time there was no thought but that Dedeagatch would also remain in Bulgarian hands. The ethnography of the entire area would certainly indicate such a solution, and Greece had her eyes fixed rather on Saloniki, southern Albania, and the remoter borders of the eastern Aegean. But with Allied victory Greece’s programme expanded so as to take in the chief elements of the Greek world, and she sought to consolidate the Greek peoples of eastern and western Thrace by including these territories within her national domain.

Ultimately she won the assent of all delegations except the American, and American opposition continued until the end, at least to the extent of not desiring to give Greece all of the territory which she eventually obtained.

American opinion favored a rectification of the Bulgarian frontier at Adrianople and Kirk-Kilisse, so as to advantage Bulgaria to some degree, and thus recognize not only the ethnic principle but also the historic fact that in the first Balkan War it was the effort of the Bulgarian army which defeated the Turkish legions, and that the flower of Bulgarian manhood fell in the sieges and campaigns against Turkish strongholds in eastern Thrace.

Having reviewed a few of the outstanding problems of the eastern Balkans we may now turn to Albania, on the other side of the peninsula, where a sharp, three-cornered conflict has raged for two years and where there still exists a problem of the first magnitude. The Albanians number 1,000,000 people. Like the states about them, they have slowly gained political self-consciousness.

Their homeland is a broken country, and a large part of the population leads a pastoral life. Its coastal towns and lowland cities are intimately tied up with the commercial systems of its neighbors, and its mountain population retains the primitive organization of the clan.

Under these circumstances it is obvious that the Albanians should not have had a strong national programme or the means to advance it. It was the will of the great powers in 1913, after the first Balkan War, that was imposed upon Albania in establishing her boundaries, and it was the will of the Allies that so long kept Italy at Valona and for a time threatened to bring Jugo-Slavia into active conflict with the northern Albanians about Scutari. Toward such a people in such a land it is difficult to frame a policy. It is easy to award independence, but it is not equally easy to believe that right use will be made of it. Jugo-Slavia and Italy are equally hated, and Greece is no exception in disfavor .

Had the terms of the secret Treaty of London of 1915 been carried out, Albania would have been divided. The central portion would have been an autonomous Mohammedan state under Italian protection; the northern part would have been under the protection of Jugo-Slavia, and the southern part was to have been divided between Greece and Italy. Koritsa would have become a Greek city, Valona an Italian stronghold and point of penetration; Scutari and the Drin valley would have become an outlet for Jugo-Slavia’s trade and all of these points would have become places for military and political conflict, for the Albanians, though having no unity of sentiment regarding a national programme, are united in the belief that they can manage their affairs better than the people about them. The Italians have been driven ; from Valona by the efforts of the Albanians themselves, and Albanian independence has been recognized by the Council of the League of Nations. By a subsequent treaty (1921) Italy is to have possession of the island of Sassens and the two peninsulas that embrace the Bay of Valona in order to complete her defense of the Adriatic.

She is also to have prior rights of a political and commercial nature, but the reality of these rights have yet to be proved.

----------------

What really happened at Paris; the story of the Peace conference, 1918-1919

For fair use only.

-

-

Memorandum of the General Council of the Macedonian Societies in Switzerland, 1919!

This Memorandum should be sent to all current Western Governments in the World, it is as if it was written today.

Our struggle has not ended, 91 years later and we are still here demanding our right amongst the nations of the World.

Source: Document F.O. 608/44, National Archives of the United Kingdom.

Macedonian Truth Organisation

Macedonian Truth Organisation

Comment

-

-

Very interesting and highly useful.Risto the Great

MACEDONIA:ANHEDONIA

"Holding my breath for the revolution."

Hey, I wrote a bestseller. Check it out: www.ren-shen.com

Comment

-

-

RTGOriginally posted by Risto the Great View PostVery interesting and highly useful.

Similarities with the Macedonian Cause - don't you think?On Delchev's sarcophagus you can read the following inscription: "We swear the future generations to bury these sacred bones in the capital of Independent Macedonia. August 1923 Illinden"

Comment

-

-

Not surprisingly, the Macedonian Cause has been around long before the MTO.

We just made it English!Risto the Great

MACEDONIA:ANHEDONIA

"Holding my breath for the revolution."

Hey, I wrote a bestseller. Check it out: www.ren-shen.com

Comment

-

-

This document has been uploaded to Wikisource:

And it has also been transliterated:

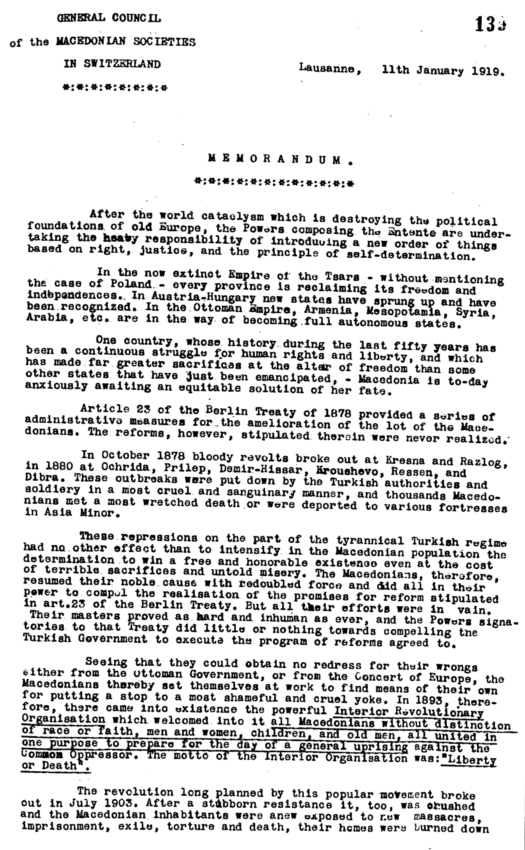

Source: Document F.O. 608/44, National Archives of the United Kingdom.GENERAL COUNCIL of the MACEDONIAN SOCIETIES IN SWITZERLAND

Lausanne, 11th January 1919

MEMORANDUM.

After the world cataclysm which is destroying he political foundations of old Europe, the Powers composing the Entente are undertaking the heavy responsibility of introducing a new order of things based on right, justice, and the principle of self-determination.

In the new extinct Empire of the Tsars - without mentioning the case of Poland - every province is reclaiming its freedom and independences. In Austria-Hungary new states have sprung up and have been recognized. In the Ottoman Empire, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Syria, Arabia, etc. are in the way of becoming full autonomous states.

One country, whose history during the last fifty years has been continuous struggle for human rights and liberty, and which has made far greater sacrifices at the altar of freedom than some other states that have just been emancipated, - Macedonia is today anxiously awaiting an equitable solution of her fate.

Article 23 of the Berlin Treaty of 1878 provided a series of administrative measures for the amelioration of the lot of the Macedonians. The reforms, however, stipulated therein where never realized.

In October 1878 bloody revolts broke out at Kresna and Razlog, in 1880 at Ochrida, Prilep, Demir-Hissar, Kroushevo, Ressen and Dibra. These outbreaks were put down by the Turkish authorities and soldiery in the most cruel and sanguinary manner, and thousands Macedonians met a most wretched death or were deported to various fortresses in Asia Minor.

These repressions on the part of the tyrannical Turkish regime had no other effect than to intensify in the Macedonian population the determination to win a free and honorable existence even at the cost of terrible sacrifices and untold misery. The Macedonians, therefore, resumed their noble cause with redoubled force and did all in their power to compel the realization of the promises for reform stipulated in the art.23 of the Berlin Treaty. But all their effort was in vain. Their masters proved as hard and inhuman as ever, and the Powers signatories to that Treaty did little or nothing toward compelling the Turkish Government to execute the program of reforms agree to.

Seeing that they could obtain no redress for their wrongs either from the Ottoman Government, or from the Concert of Europe, the Macedonians thereby set themselves at work to find means of their own for putting a stop to a most shameful and cruel yoke. In 1893, therefore, there came into existence the powerful Interior Revolutionary Organization which welcomed into it all Macedonians without distinction of race or faith, men and women, children, and old men, all united in one purpose to prepare for the day of a general uprising against the Common Oppressor. The motto of the Interior Organization was: "Liberty or Death".

The revolution long planned by this popular movement broke out in July 1903. After a stubborn resistance it, too, was crushed and the Macedonian inhabitants were anew exposed to new massacres, imprisonment, exile, torture and death, their homes were burned down and destroyed, and their property pillaged, carried away or confiscated. The terrible consequences from that insurrection were 198 villages completely destroyed, hundreds of others sacked and pillaged, 13,221 houses burned, 170,000 people left withoug a shelter in the full blast of winter.

What deserves to be noted in this insurrectionary action is the character of the proclamation issued for the occasion by the Revolutionary Organization. "We resort to arms", the proclamation ran, "against the tyranny and inhuman bondage. We rise in the name of liberty and justice; our cause, consequently, stands above the narrow conception of nationality and religion. What we demand is liberty and independence for all".

The Revolutionary Committee at the same time had spread abroad a second manifest in which were set forth the demands of the Macedonian people, which were: 1) The nomination, with the ascent of the Great Powers, of a Christian Governor-General, completely independent of the Sublime Porte, 2) The establishment of a collective and permanent international Control over the administration of Macedonia.

With this proclamation addressed to the world the leaders of the Revolutionary movement emphasized the fact that the chief aim of their struggle was the realization of the principle of "Macedonia for the Macedonians".

The Macedonian insurrection of 1903, through barren of any beneficial result for the unhappy country, at least frightened the emperors of Russia and Austria, who soon, on September 30th following, met and drew the famous "Mursteg Reform Plan" for Macedonia, which was simply intended to deceive the world and retard the liquidation of the eastern Question until a moment favoring their political designs. The Macedonian finding their hopes frustrated again, had no other alternative left, but to renew their struggle against the Turk.

The situation in the Balkans after the so-called Ilinden Insurrection grew worse and worse. England, in the meanwhile, stepped in and at the royal interview between king Edward VII and Emperor Nicholas at Reval in 1908, was drawn the "Reval Program of Reforms". Germany, however, finding such a scheme not to her liking, took the side of Abdul Hamid and encouraged him in his decision to resist the introduction of any reforms in his domains.

The enthusiasm created by the inauguration of the young Turk Regime and its constitution was of very short duration. All Christian peoples in the Ottoman Empire soon perceived that the Huriet was a sham and that the leaders of the young Turk Party had no sincere desire to see the Empire regenerated. The traditional system of discrimination, repression, persecution and extermination were now employed with more refined and concerted methods. Local revolts occurred in various parts of Macedonia, which were suppressed in the usual Turkish way.

We may here remark that the failure of the insurrectionary actions undertaken by the Macedonians was mainly due to the rivalry between Russia and Austria-Hungary, which later on manifested itself in the conflicts between the Balkan states. The policy of Russia and Austria-Hungary was that by sowing discord among the small Balkan states to further their own selfish designs in the Near East.

Austria by virtue of secret treaty concluded between her and Serbia in 1880 succeeded in exacting the promise from the latter to renounce her interest in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in return for which Austria engaged herself to support her claims in Macedonia. The echo of this transaction was the fatal Bucharest Treaty of 1913. The greatest blunder and even crime committed by the diplomatists of the Balkan states was their division of Macedonia without consulting the wish of its population itself.

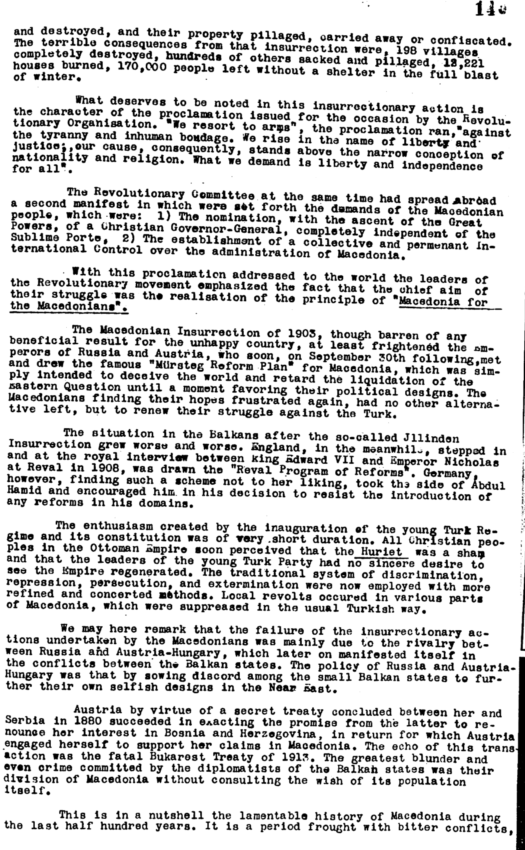

This is in a nutshell the lamentable history of Macedonia during the last half hundred years. It is a period fraught with bitter conflicts, persecution, wholesale butchery, tears, and devastations. What other land has shown more stubbornness, dogged tenacity, and fought more desperately for human rights and freedom? Even the frightful experiences and suffering of the Armenian people, in the course of the last decades, fade before the martyrdom the Macedonians were fated to go through.

In pointing to the above record of trials and sufferings in their struggle for liberty, it is not evident that the Macedonians have showed themselves worthy of being accorded the right of deciding their own fate - a privilege granted to Dalmatians, Croats, Slovenes, Tchecks, Armenians, Arabs, etc.? Must the Macedonian people be handled as chattels by their neighbors? We the Macedonians are firmly convinced that the great Democracies of the XX century, will come to our aid in our struggle for self-determination.

What we ask for is not only our right, but also our imperative duty; it is the demand of the Macedonians that their voice may be heard before their future destiny is decided.

We, the general Council of the Macedonian Societies in Switzerland, are fully convinced that a proper, just and lasting solution of the Macedonian Question may be found by giving the Macedonian people, too, the opportunity to freely declare its will a to its future form of government, which may be effected:

1. By the occupation of the Country by only American, French, English, and Italian troops;

2. By permitting all Macedonian refugees abroad, without distinction of race and religion, to return to their homes unmolested, and to be allowed to participate in the organization and management of their Country's state affairs;

3. By entrusting the local administration of Macedonia in the hands of the native inhabitants, under the control of the Army of Occupation.

Firmly believing that the decisions taken in the future Peace Conference will be guided by actual facts, equity and impartiality, we gladly and unreservedly entrust our fate in the hands of it members, and avail ourselves of the present opportunity to wish the Peace Congress full success in its grand and epochal undertaking.

President, Stoyan Citkoff, Former Ottoman Senator.

Secretary, Constantine Stephanove (MA) (University Professor)

Stamp reads: DES SOCIETES MACEDONIENNE, LAUSANNE

I would like to thank GStojanov from MakNews for his splendid work on the transliteration.Macedonian Truth Organisation

Comment

-

-

The signatories are:Originally posted by sydney View Posti can't make it out, please confirm the signatories of the memo. thanks.

President, Stoyan Citkoff, Former Ottoman Senator.

Secretary, Constantine Stephanove (MA) (University Professor)

Stamp reads: DES SOCIETES MACEDONIENNE, LAUSANNEMacedonian Truth Organisation

Comment

-

-

Macedonian Student Goes Through Yale By Running A Trolley Car

( Originally Published 1902 )

Yale University some little time ago, the degree of Master of Arts was conferred upon Constantine Demeter Stephanove, a native of Bausko, Macedonia. The remarkable manner in which he supported himself during the seven years of his student life at Yale is described by him in an interview which is as follows :

" The hardest work I have done was not in college. I left my home when I was sixteen. My mother did not wish me to come, but I was fired with an ambition to help my native land, and I saw that education was the first necessity of my people.

" I came to this country and went up into Canterbury, Connecticut, where I secured work on a farm. There I saw some of the hardest work I have ever done. I milked ten cows night and morning, and was busy from the time I arose at daylight until dusk.

" Here I learned the language, and then I went to the preparatory school at Monson, Massachusetts.

" I graduated from the Monson Academy in 1895, and came at once to Yale, where I began my studies. I waited on the table for a living during the first year or two, and later secured work on the trolley.

" I don't suppose half my classmates imagined I was a trolley conductor, unless they saw me, and many of the professors would be surprised to hear of it, I am sure. And I doubt very much if many of my trolley friends knew that I was in Yale until they read of it recently.

" On my graduation in 1899 I was still dissatisfied with my education and determined to keep on. Now that I have secured my degree and can speak the language fairly well, I intend to complete the work at a German University.

" You may think it strange, but I have found five hours a day sufficient for sleep.

" I have been on what is known as the ` owl ' car, which runs all night, after all the other cars have stopped. I had to go on duty at midnight and work until 7:30 in the morning. After my day at college I would Come home between 6 and 7 in the evening and allow nothing to interfere with my going to bed. Then I would sleep until nearly midnight, when I would get up, get my bite to eat and be off for the car. We usually made half a dozen trips at night, and I have seen all sorts of people.

" In the morning when I finished I would continue my studies, which I had partly completed the afternoon previous, and be ready for the classroom. I have given all my time to work and study ; my exercise and recreation I obtained on the trolley."

The struggles and victory of this young man remind us very much of the Macedonians of olden time, who arose with sublime heroism to subdue the people in letters and in morals.

Ile has been brave, not like his fellow-countrymen under Philip, to conquer men with swords of steel, but to wield over them the gentle sceptre of the degree at Yale. The great sea, a foreign land, new customs, a strange language and poverty, are barriers that would have kept a boy of average ability and average courage in a very narrow circle ; but this splendidly endowed young man counted them as nothing, and made them even tributary to his development and promotion. The most beautiful feature of his heroic conduct is the fact that his efforts have been to prepare himself for unselfish service for others; he has gone to all this trouble through these many years that he may be enabled to return to his native land qualified to teach his own people. There were so many difficulties between the Macedonian boy and truth and love.

It is the pride of American educational life that so many poor young men work their way through college, and the lessons of enterprise, industry, self-reliance and self-denial are about as valuable as those learned from books and professors, in the development of manhood. It is also a matter of congratulation that so many poor young men put themselves through college that they may devote themselves unselfishly to the interest of others."Ido not want an uprising of people that would leave me at the first failure, I want revolution with citizens able to bear all the temptations to a prolonged struggle, what, because of the fierce political conditions, will be our guide or cattle to the slaughterhouse"

GOTSE DELCEV

Comment

-

-

Dats, thank you for the article, good work, aside from Mirka Ginova, women are the unsung heroes for the Macedonian cause"The moral revolution - the revolution of the mind, heart and soul of an enslaved people, is our greatest task."__________________Gotse Delchev

Comment

-

-

Originally posted by julie View PostDats, thank you for the article, good work, aside from Mirka Ginova, women are the unsung heroes for the Macedonian cause

Link to the full article

Comment

-

Comment