Democratic changes and the gain of independence

In 1987 and 1988, a series of clashes between the emerging civil society and the Communist regime culminated with the so-called Slovenian Spring. A mass democratic movement, coordinated by the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights, pushed the Communists in the direction of democratic reforms. These revolutionary events in Slovenia pre-dated by almost one year the Revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe, but went largely unnoticed by the international observers.

At the same time, the confrontation between the Slovenian Communists and the Serbian Communist Party, dominated by the charismatic nationalist leader Slobodan Milošević, became the most important political struggle in Yugoslavia. Bad economic performance of the Federation, and the rising clashes between the different republics, created a fertile soil for the rise of secessionist ideas among Slovenes, both anti-Communists and Communists. In January 1990, the Slovenian Communists left the Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in protest against the domination of the Serb nationalist leadership, thus effectively dissolving the Yugoslav Communist Party, the only remaining institution holding the country together.

In April 1990, the first free and democratic elections were held, and the Democratic Opposition of Slovenia defeated the former Communist party. A coalition government led by the Christian Democrat Lojze Peterle was formed, and began economic and political reforms that established a market economy and a liberal democratic political system. At the same time, the government pursued the independence of Slovenia from Yugoslavia. In December 1990, a referendum on the independence of Slovenia was held, in which the overwhelming majority of Slovenian residents (around 89%) voted for the independence of Slovenia from Yugoslavia. Independence was declared on 25 June 1991. A short Ten-Day War followed, in which the Slovenian forces successfully rejected Yugoslav military interference.

After 1990, a stable democratic system evolved, with economic liberalization and gradual growth of prosperity. Slovenia joined NATO on 29 March 2004 and the European Union on 1 May 2004. Slovenia was the first post-Communist country to hold the Presidency of the Council of the European Union, for the first six months of 2008.

Contributions to the Slovenian National Program (Slovene: Prispevki za slovenski nacionalni program), also known as Nova revija 57, was a special issue of the alternative intellectual journal Nova revija, published in January 1987. It contained 16 articles by non-Communist and anti-Communist dissidents in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia. It was issued as a reaction to the Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts and to the rising centralist aspirations within the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

The authors of the Contributions analyzed the different aspects of political and social conditions in Slovenia, especially in its relations to Yugoslavia. Most of the contributors called for the establishment of a sovereign, democratic and pluralist Slovenian state, although direct demands for independence were not uttered.

The publication provoked a scandal throughout former Yugoslavia. The editors of Nova revija were called to defend themselves in a state-sponsored public discussion, organized by the Socialist Alliance of the Working People. The editorial board was forced to step down, but no public prosecution was conducted again any of the authors, and the journal could continue issuing without restrictions.

The publications is usually considered as the direct prelude of the so-called Slovenian Spring, a mass political movement for democratization that started the following year by protests against the JBTZ trial.

In the following years, many of the authors of the Contributions became active in the political parties of the DEMOS coalition, especially the Slovenian Democratic Union.

Disintegration of Yugoslavia

The independence of Slovenia came about as a result of the rise of nationalism among the [nations of SFRY] and the dissolution of Yugoslavia resulting from it. Crisis emerged in Yugoslavia with the weakening of communism in Eastern Europe towards the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s. In Yugoslavia, the federal Communist Party, officially called Alliance or League of Communists, was losing its ideological dominance.

At the same time, nationalist and separatist ideologies were on the rise in the late 1980s throughout Yugoslavia. This was particularly noticeable in Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. To a lesser extent, nationalist and separatist ideologies were on the rise in Slovenia and […] Macedonia. Slobodan Milošević's rise to power in Serbia, and his rhetoric in favour of the unity of all Serbs, was responded to with nationalist movements in other republics, particularly Croatia and Slovenia. These Republics began to seek greater autonomy within the Federation, including confederative status and even full independence. Nationalism also grew within the still ruling League of Communists. So the weakening of the communist regime allowed nationalism to become a more powerful force in Yugoslav politics. In January 1990, the League of Communists broke up on the lines of the individual Republics.

In March 1989, the crisis in Yugoslavia deepened after the adoption of certain amendments to the Serbian constitution which allowed the Serbian republic's government to re-assert effective power over the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. The Serb government claimed that the previous situation had been unjust in allowing these provinces to be involved in the administration of Serbia Central whilst Serbia Central had no control over what happened in these two autonomous provinces. Serbia, under president Slobodan Milošević, thus gained control over three out of eight votes in the Yugoslav presidency. With additional votes from Montenegro and, occasionally, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia was now even able to influence heavily any decision of the federal government. This situation led to objections in other republics and to calls for a reform of the Yugoslav Federation.

At the 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, on 20 January 1990, the delegations of the republics could not agree on the main issues in the Yugoslav federation. As a result, the Slovenian and Croatian delegates left the Congress. The Slovenian delegation, headed by Milan Kučan, demanded democratic changes and a looser federation, while the Serbian delegation, headed by Milošević, opposed this point-blank. This is considered the beginning of the end of Yugoslavia.

In 1987 and 1988, a series of clashes between the emerging civil society and the Communist regime culminated with the so-called Slovenian Spring. A mass democratic movement, coordinated by the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights, pushed the Communists in the direction of democratic reforms. These revolutionary events in Slovenia pre-dated by almost one year the Revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe, but went largely unnoticed by the international observers.

At the same time, the confrontation between the Slovenian Communists and the Serbian Communist Party, dominated by the charismatic nationalist leader Slobodan Milošević, became the most important political struggle in Yugoslavia. Bad economic performance of the Federation, and the rising clashes between the different republics, created a fertile soil for the rise of secessionist ideas among Slovenes, both anti-Communists and Communists. In January 1990, the Slovenian Communists left the Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in protest against the domination of the Serb nationalist leadership, thus effectively dissolving the Yugoslav Communist Party, the only remaining institution holding the country together.

In April 1990, the first free and democratic elections were held, and the Democratic Opposition of Slovenia defeated the former Communist party. A coalition government led by the Christian Democrat Lojze Peterle was formed, and began economic and political reforms that established a market economy and a liberal democratic political system. At the same time, the government pursued the independence of Slovenia from Yugoslavia. In December 1990, a referendum on the independence of Slovenia was held, in which the overwhelming majority of Slovenian residents (around 89%) voted for the independence of Slovenia from Yugoslavia. Independence was declared on 25 June 1991. A short Ten-Day War followed, in which the Slovenian forces successfully rejected Yugoslav military interference.

After 1990, a stable democratic system evolved, with economic liberalization and gradual growth of prosperity. Slovenia joined NATO on 29 March 2004 and the European Union on 1 May 2004. Slovenia was the first post-Communist country to hold the Presidency of the Council of the European Union, for the first six months of 2008.

Contributions to the Slovenian National Program (Slovene: Prispevki za slovenski nacionalni program), also known as Nova revija 57, was a special issue of the alternative intellectual journal Nova revija, published in January 1987. It contained 16 articles by non-Communist and anti-Communist dissidents in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia. It was issued as a reaction to the Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts and to the rising centralist aspirations within the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

The authors of the Contributions analyzed the different aspects of political and social conditions in Slovenia, especially in its relations to Yugoslavia. Most of the contributors called for the establishment of a sovereign, democratic and pluralist Slovenian state, although direct demands for independence were not uttered.

The publication provoked a scandal throughout former Yugoslavia. The editors of Nova revija were called to defend themselves in a state-sponsored public discussion, organized by the Socialist Alliance of the Working People. The editorial board was forced to step down, but no public prosecution was conducted again any of the authors, and the journal could continue issuing without restrictions.

The publications is usually considered as the direct prelude of the so-called Slovenian Spring, a mass political movement for democratization that started the following year by protests against the JBTZ trial.

In the following years, many of the authors of the Contributions became active in the political parties of the DEMOS coalition, especially the Slovenian Democratic Union.

Disintegration of Yugoslavia

The independence of Slovenia came about as a result of the rise of nationalism among the [nations of SFRY] and the dissolution of Yugoslavia resulting from it. Crisis emerged in Yugoslavia with the weakening of communism in Eastern Europe towards the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s. In Yugoslavia, the federal Communist Party, officially called Alliance or League of Communists, was losing its ideological dominance.

At the same time, nationalist and separatist ideologies were on the rise in the late 1980s throughout Yugoslavia. This was particularly noticeable in Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. To a lesser extent, nationalist and separatist ideologies were on the rise in Slovenia and […] Macedonia. Slobodan Milošević's rise to power in Serbia, and his rhetoric in favour of the unity of all Serbs, was responded to with nationalist movements in other republics, particularly Croatia and Slovenia. These Republics began to seek greater autonomy within the Federation, including confederative status and even full independence. Nationalism also grew within the still ruling League of Communists. So the weakening of the communist regime allowed nationalism to become a more powerful force in Yugoslav politics. In January 1990, the League of Communists broke up on the lines of the individual Republics.

In March 1989, the crisis in Yugoslavia deepened after the adoption of certain amendments to the Serbian constitution which allowed the Serbian republic's government to re-assert effective power over the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. The Serb government claimed that the previous situation had been unjust in allowing these provinces to be involved in the administration of Serbia Central whilst Serbia Central had no control over what happened in these two autonomous provinces. Serbia, under president Slobodan Milošević, thus gained control over three out of eight votes in the Yugoslav presidency. With additional votes from Montenegro and, occasionally, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia was now even able to influence heavily any decision of the federal government. This situation led to objections in other republics and to calls for a reform of the Yugoslav Federation.

At the 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, on 20 January 1990, the delegations of the republics could not agree on the main issues in the Yugoslav federation. As a result, the Slovenian and Croatian delegates left the Congress. The Slovenian delegation, headed by Milan Kučan, demanded democratic changes and a looser federation, while the Serbian delegation, headed by Milošević, opposed this point-blank. This is considered the beginning of the end of Yugoslavia.

Shortly after, Slovenia and Croatia entered into the process towards independence. The first free elections were scheduled in Croatia and Slovenia. Defying the politicians in Belgrade, Slovenia embraced democracy and opened its society in the cultural, civic, and economic spheres to a degree almost unprecedented in the communist world.

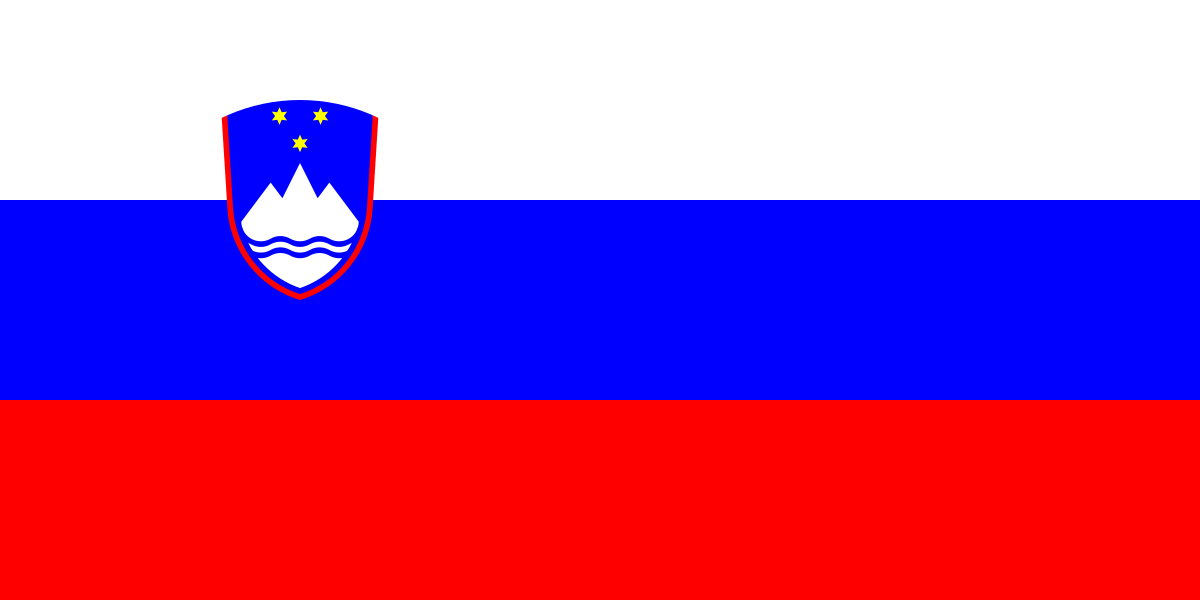

On December 23, 1990, 88% of Slovenia's population voted for independence in a plebiscite, and on June 25, 1991, the Republic of Slovenia declared its independence. On June 26, 1991 Croatia and Slovenia recognized each other as independent states.[14]

On December 23, 1990, 88% of Slovenia's population voted for independence in a plebiscite, and on June 25, 1991, the Republic of Slovenia declared its independence. On June 26, 1991 Croatia and Slovenia recognized each other as independent states.[14]

A 11-day war with Yugoslavia followed (June 26, 1991 - July 6, 1991). The Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) forces withdrew after Slovenia demonstrated stiff resistance to Belgrade. The conflict resulted in relatively few casualties: 67 people were killed according to statistics compiled by the International Red Cross, of which most (39) were JNA soldiers.

Comment