These once ravaged golden Asia, and brought

slavery upon the Greeks. Now ownerless

they lie by the pillars of the temple of Zeus,

spoils of boastful Macedonia (1.13.2).

slavery upon the Greeks. Now ownerless

they lie by the pillars of the temple of Zeus,

spoils of boastful Macedonia (1.13.2).

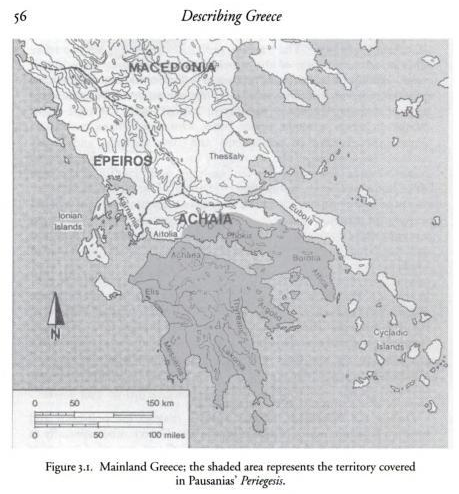

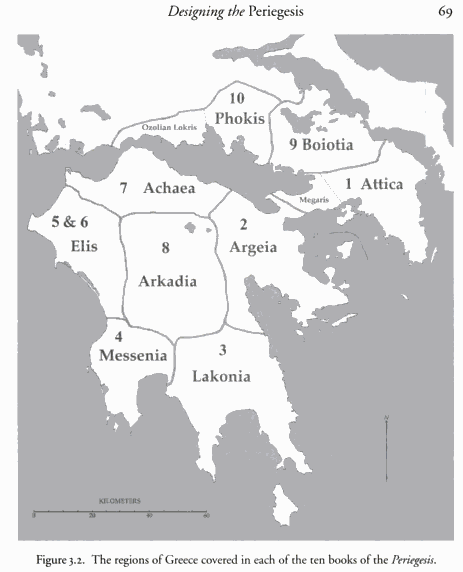

The following analysis is based on the works of an ancient writer called Pausanias (2nd cent. ad), which are entitled ‘Description of Greece’. Correctly, the country of Macedonia is not one of the regions included in this ‘Description of Greece’. The regions considered as ‘Greece’ are Attica, Corinth, Laconia, Messenia, Elis, Achaia, Arcadia, Boeotia and Phocis. As with many of the ancient sources, some texts tend to be vague in detail or contradictory where it concerns certain passages, either out of necessity or will, and Pausanias, echoing similar sentiments to Herodotus, remarks that "most matters of Greek history have come to be disputed" (4.2.3), and that there are "many untruths believed by the Greeks" (9.30.4).

With this in mind when considering the Pausanias texts, let us assess the Greek view first, and then subsequently dismiss it. There is a passage where reference is made to Alexander swearing by the "gods of Greece" (6.18.3), although it is known that most of the gods worshipped during antiquity were not of ‘Greek’ origin, and further still, even the "Greek legends generally have for the most part different versions" (9.16.7). Given that most authors were Greeks themselves, the reference to the gods as ‘Greek’ eventually became the norm. There is another part of the text that cites an oracle that states "Ye Macedonians, boasting of your Argive kings" (7.8.9), a reference to the mythical descent claimed by the Macedonian kings, a common practice by Greek, Macedonian, Persian, Scythian and other rulers during antiquity. Indeed, the apparent ‘Greek’ connection of the Macedonian kings rested solely on this myth, which is also evident in the fact that even when they were finally permitted to compete in the Olympic games, they could so only as 'Heraklides', ie; descendants of Herakles, and not as Macedonians. It would only be several years later that the Macedonian nobility were allowed to partake in the Olympic games, after which the Romans, another non-Greek people, also joined in participation. Countless examples can be given of the multi-dimensional and heterogeneous character of the ancient world that is all too often inaccurately referred to today as the ancient ‘Greek’ world. The art of mathematics have their origins in Egypt, many of the gods are Pelasgian, the alphabet is of Phoenician origin, certain hymns and rituals have Thracian origins, and so forth.

Pausanias also states the following, with regard to the Macedonian participation in Greek organisations:

The Phocians were deprived of their share in the Delphic sanctuary and in the Greek assembly, and their votes were given by the Amphictyons to the Macedonians (10.3.3)

They say that Amphictyon himself summoned to the common assembly the following tribes of the Greek people:--Ionians, Dolopes, Thessalians, Aenianians, Magnesians, Malians, Phthiotians, Dorians, Phocians, Locrians who border on Phocis, living at the bottom of Mount Cnemis. But when the Phocians seized the sanctuary, and the war came to an end nine years afterwards, there came a change in the Amphictyonic League. The Macedonians managed to enter it, while the Phocian nation and a section of the Dorians, namely the Lacedaemonians, lost their membership, the Phocians because of their rash crime, the Lacedaemonians as a penalty for allying themselves with the Phocians (10.8.2).

Judging by the complete content of his texts, Pausanias does not seem to indicate a Greek origin for Macedonia and the Macedonian people. In several instances there is a clear distinction made between the Macedonians and Greeks, and countless remarks about the shared hatred between the two peoples. The detriment caused to the Greeks by the Macedonians is clearly demonstrated in his works, the loss of freedom and politicial power, their plundered and garrisoned cities, the loss of their ancient liberties, being forced into humiliating circumstances, and the general destruction of their way of life. All of this made the Greeks easy prey for future invaders such as the Romans and the Celts, defining most Macedonian actions as decidedly un-Greek. As a result of this, Greeks tended to revolt periodically against Macedonian rule, after the death of Alexander "the Greeks had raised a second war against the Macedonians" (4.28.3). Such was their contempt for the Macedonians, that they welcomed Rome to intercede in their favour, "those who destroyed the Macedonian empire were the Romans" (7.7.8), further corroborated by Plutarch who remarked that "the Romans came not to fight against the Greeks, but for the Greeks, against the Macedonians" (Flaminius). Here are some more examples of Greek efforts and pleas towards their Roman saviours:

Already, in my account of Attica I have described the alliances of Greeks and barbarians with the Athenians against Philip, and how the weakness of their allies urged the Athenians to seek help from Rome (7.7.7).

At the appeal of Athens the Romans despatched an army under Otilius, to give him the name by which he was best known (7.7.8).

Titus, the Roman governor, who had a commission from Rome to give all Greeks their freedom, promised to give back to Elateia its ancient constitution, and by messengers made overtures to its citizens to secede from Macedonia……..the Romans gave them their freedom (10.34.4).

Most of their cities Philip captured……..But when on the death of Alexander the Macedonians chose Aridaeus to be their king, though the whole empire had been entrusted to Antipater, the Athenians now thought it intolerable if Greece should be for ever under the Macedonians, and themselves embarked on war besides inciting others to join them (1.25.3).

Moreover, as all the Greeks were afraid of the Macedonians and of Antigonus, the guardian of Philip, the son of Demetrius, he induced the Sicyonians, who were Dorians, to join the Achaean League (2.8.4).

Greece, that still stood firm, was shaken to its foundations by this war, and afterwards, when the structure had given way and was far from sound, was finally overthrown by Philip the son of Amyntas (3.7.11).

.........but when Philip the son of Amyntas did all the harm to Greece that has been related......(4.28.4).

When Philip, the son of Demetrius, reached man's estate, and Antigonus without reluctance handed over the sovereignty of the Macedonians, he struck fear into the hearts of all the Greeks. He copied Philip, the son of Amyntas........(7.7.5).

He also occupied with garrisons three towns to be used as bases against Greece, and in his insolent contempt for the Greek people he called these cities the keys of Greece (7.7.6).

This Leosthenes at the head of the Athenians and the united Greeks defeated the Macedonians in Boeotia and again outside Thermopylae forced them into Lamia over against Oeta, and shut them up there (1.1.2).

This Archias was a Thurian who undertook the abominable task of bringing to Antipater for punishment those who had opposed the Macedonians before the Greeks met with their defeat in Thessaly (1.8.3).

The cities that took part were, of the Peloponnesians, Argos, Epidaurus, Sicyon, Troezen, the Eleans, the Phliasians, Messene; on the other side of the Corinthian isthmus the Locrians, the Phocians, the Thessalians, Carystus, the Acarnanians belonging to the Aetolian League. The Boeotians, who occupied the Thebaid territory now that there were no Thebans left to dwell there, in fear lest the Athenians should injure them by founding a settlement on the site of Thebes, refused to join the alliance and lent all their forces to furthering the Macedonian cause (1.25.4).

Finally the Messenians formed an alliance with Philip the son of Amyntas and the Macedonians; it was this, they say, that prevented them from taking part in the battle which the Greeks fought at Chaeroneia. They refused, however, to bear arms against the Greeks (4.28.2).

They joined Philip's attack on the Lacedaemonians because of their old hatred of that people, but on the death of Alexander they fought on the side of the Greeks against Antipater and the Macedonians (5.4.9).

Though they did not fight on the Greek side against Philip and the Macedonians at Chaeroneia, nor later in Thessaly against Antipater, yet they did not actually range themselves against the Greeks (8.6.2).

When day dawned and the inhabitants had realized the danger that beset them, they were at first under the impression that the Lacedaemonians had forced an entry into the town, and attacked them more recklessly owing to their ancient hatred. But when they discovered from their equipment and speech that it was the Macedonians and Demetrius the son of Philip, they were filled with great fear, when they considered the Macedonian training in warfare and the good fortune which they saw that they enjoyed in all their ventures (4.29.3).

For the disaster at Chaeronea was the beginning of misfortune for all the Greeks, and especially did it enslave those who had been blind to the danger and such as had sided with Macedon (1.25.3).

When Philip the son of Amyntas would not let Greece alone, the Eleans, weakened by civil strife, joined the Macedonian alliance, but they could not bring themselves to fight against the Greeks at Chaeroneia (5.4.9).

This building is on the left of the exit over against the Town Hall. It is made of burnt brick and is surrounded by columns. It was built by Philip after the fall of Greece at Chaeroneia (5.20.10).

Of the wars waged afterwards by the confederate Greeks, the Achaeans took part in the battle of Chaeroneia against the Macedonians under Philip (7.6.5).

As they were retreating to the Peloponnesus the Romans under Metellus fell upon them near Chaeroneia. It was then that the vengeance of the Greek gods overtook the Arcadians, who were slain by the Romans on the very spot on which they had deserted from the Greeks who were struggling at Chaeroneia against the Macedonians under Philip (7.15.6).

I have already said in my history of Attica that the defeat at Chaeroneia was a disaster for all the Greeks………..(9.6.5).

The Thebans assert that Linus was buried among them, and that after the Greek defeat at Chaeroneia, Philip the son of Amyntas, in obedience to a vision in a dream, took up the bones of Linus and conveyed them to Macedonia (9.29.8).

On a pillar is a statue of Isocrates, whose memory is remarkable for three things: his diligence in continuing to teach to the end of his ninety-eight years, his self-restraint in keeping aloof from politics and from interfering with public affairs, and his love of liberty in dying a voluntary death, distressed at the news of the battle at Chaeronea (1.18.8).

It was the Athenians and Thebans who brought back the inhabitants before the disaster of Chaeroneia befell the Greeks (10.3.3).

Below is some information about the populations of a couple of historically significant regions in Greece during Romans times:

Corinth is no longer inhabited by any of the old Corinthians, but by colonists sent out by the Romans……(2.1.2).

.......while Delos, once the common market of Greece, has no Delian inhabitants......(8.33.2).

Below are some examples of non-Greeks that were involved in the so-called ancient 'Greek' world:

A Roman senator won an Olympic victory........(5.20.8).

We know of no Roman, either commoner or senator, who gave a votive offering to a Greek sanctuary before Mummius, and he dedicated at Olympia a bronze Zeus from the spoils of Achaia.........(5.24.4).

A bronze head of the Paeonian bull called the bison was sent to Delphi by the Paeonian king Dropion, son of Leon (10.13.1).

Although cited above, I will end this article with the following quote:

...........all the Greeks were afraid of the Macedonians (2.8.4).

Comment