This should make for an interesting topic now that we have someone of Germanic origin who can shed some more light from the other end of the spectrum. I recall conversations in the past with Slovak regarding this issue and came to some sort of consensus whereby it would have to be accepted that the Goths may have consisted of both Slavic and Germanic peoples.

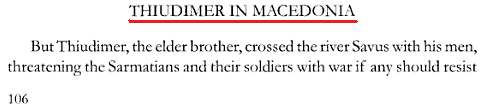

Most western sources consider them Germanic, but much of the evidence we have suggests a heavy Slavic element. Their locations of travel and settlement in Europe, personal names, etc.

Goths reached as far as Iberia, the Balkans and other parts of Europe, where are all the Germanic placenames in Iberia and the Balkans? Slavic placenames are found in nearly all countries of Europe, even Iberia, in many instances as slaves or members of another group of people, as recently cited by Risto the Great on another thread:

Jordanes, a Goth himself, considers the Goths and Getae one in the same, this is also confirmed by Procopius who states that some "called these nations Getic". I see that an old article of mine about the Getae is being used over at the Macedonian Brotherhood, another group of dedicated and proud Macedonians.

Here are some of the Gothic/Getic names mentioned by Jordanes:

Telefus, Gradivus, Filimer, Thuidimer, Valamir and Vidimer.

Do these seem more Slavic or Germanic?

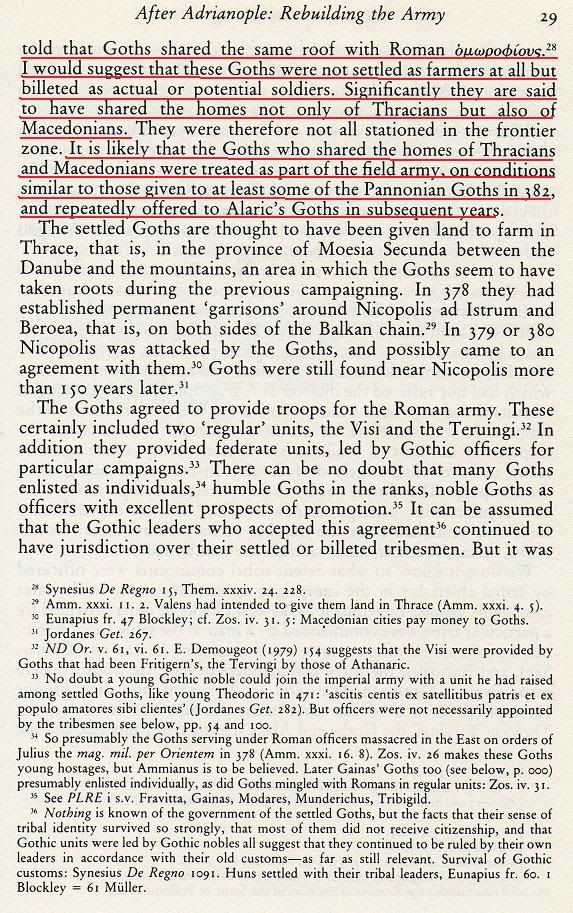

It is interesting to note that Jordanes speaks of the Goths/Getae as inhabiting lands where Macedonians and Thracians dwelt, where the Slavic-speaking people in this region live, which is also further supported by Theophylact Simocatta who states that the Getic name is another older way of referring to the Slavic rebels.

I think that's enough to kick off this topic, let's hear some thoughts.

Most western sources consider them Germanic, but much of the evidence we have suggests a heavy Slavic element. Their locations of travel and settlement in Europe, personal names, etc.

Goths reached as far as Iberia, the Balkans and other parts of Europe, where are all the Germanic placenames in Iberia and the Balkans? Slavic placenames are found in nearly all countries of Europe, even Iberia, in many instances as slaves or members of another group of people, as recently cited by Risto the Great on another thread:

Jordanes, a Goth himself, considers the Goths and Getae one in the same, this is also confirmed by Procopius who states that some "called these nations Getic". I see that an old article of mine about the Getae is being used over at the Macedonian Brotherhood, another group of dedicated and proud Macedonians.

Here are some of the Gothic/Getic names mentioned by Jordanes:

Telefus, Gradivus, Filimer, Thuidimer, Valamir and Vidimer.

Do these seem more Slavic or Germanic?

It is interesting to note that Jordanes speaks of the Goths/Getae as inhabiting lands where Macedonians and Thracians dwelt, where the Slavic-speaking people in this region live, which is also further supported by Theophylact Simocatta who states that the Getic name is another older way of referring to the Slavic rebels.

I think that's enough to kick off this topic, let's hear some thoughts.

Strange but true.

Strange but true.

Comment