THE UNKNOWN PAEONIAN WORLD

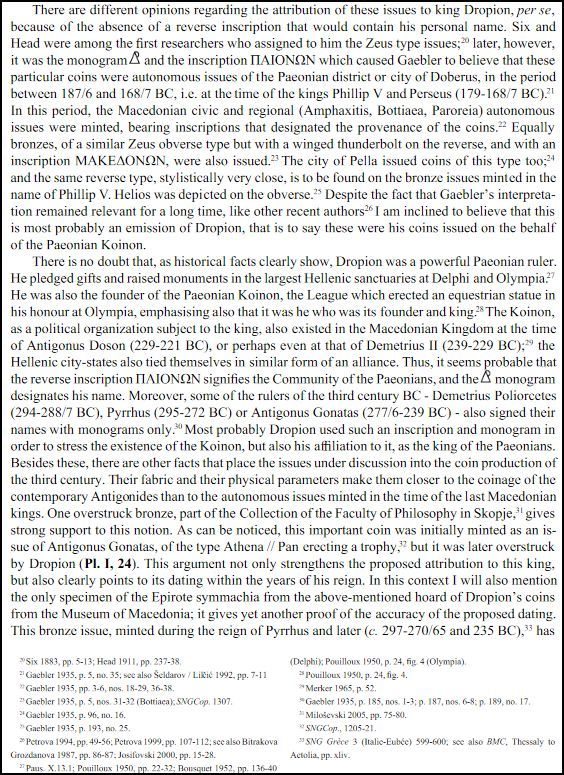

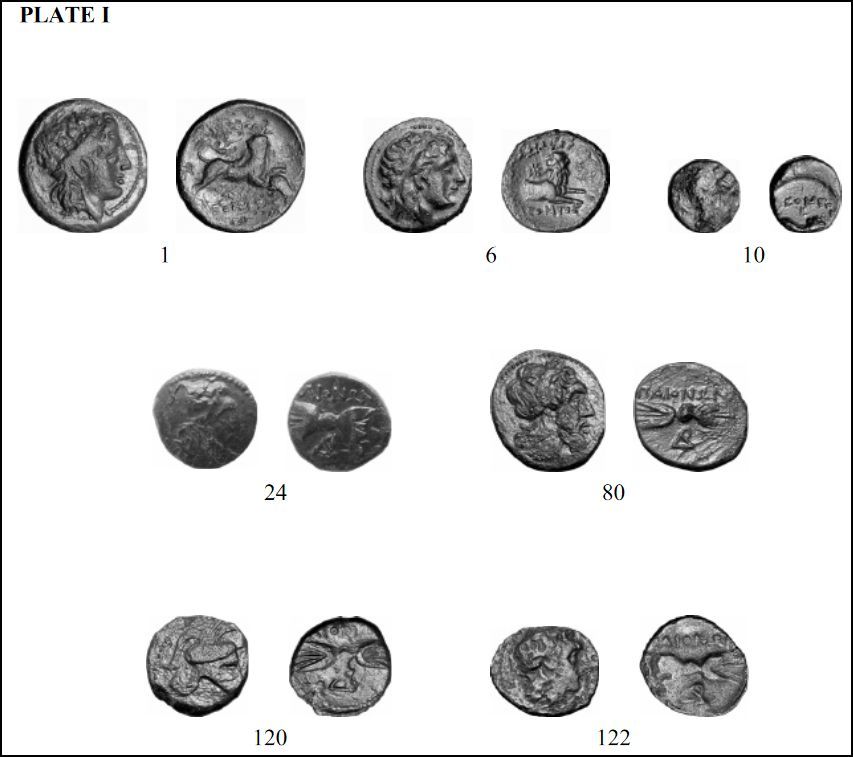

Martin Kubelka, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University Skopje, Department of Archaeology

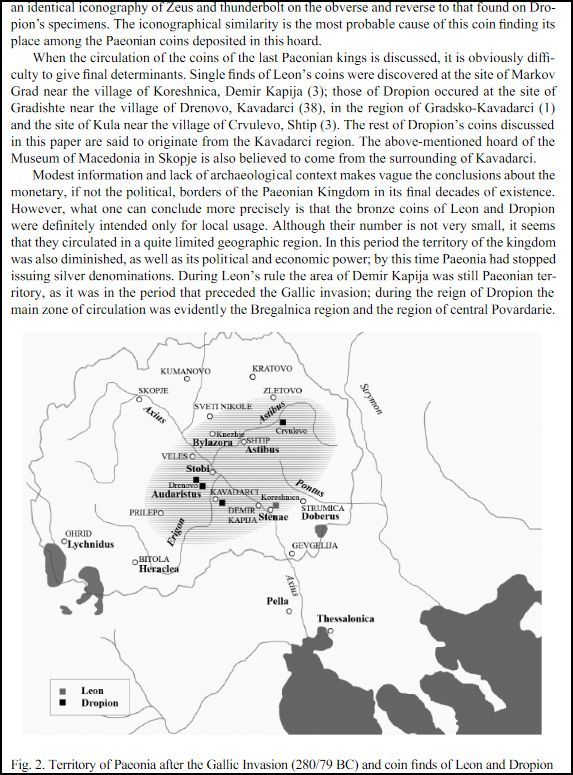

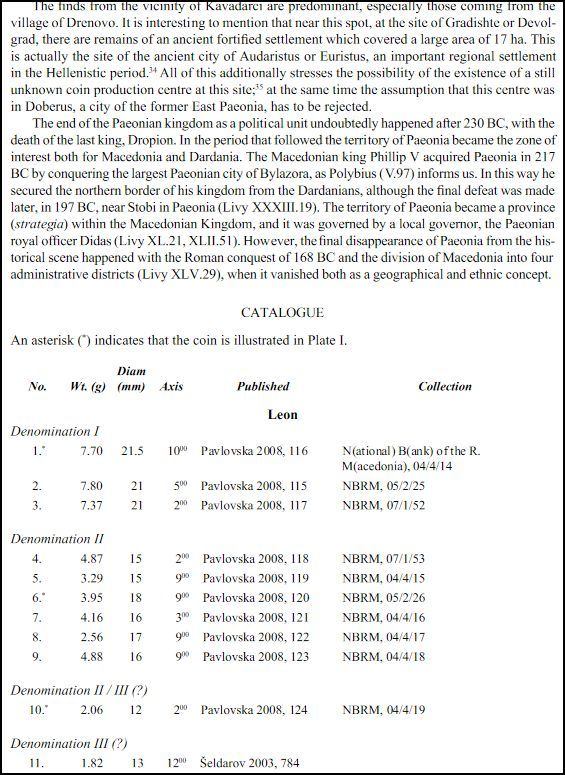

The territory of the present-day Republic of Macedonia and the parts of the neighbouring countries of Bulgaria and Greece were settled by Paeonian tribes towards the end of the second and during the first millennium BC. During the Classical and Hellenistic period some of these tribes expanded their tribal in settlements and became kingdoms. One of the most important features of Paeonian economic, political and cultural life is the early mintage of coins dated the 6th century BC by whichthey got access to the civilized world. In the period between the 6th and the 3rd century BC, minting became an important element which separated Paeonians from the barbarian tribes who lived north of them.

“THE PAEONIANS WITH CURVED BOWS” LED BY “PYRAICHMES FROM THE BROAD AXIUS” – HOMER “THE ILIAD”

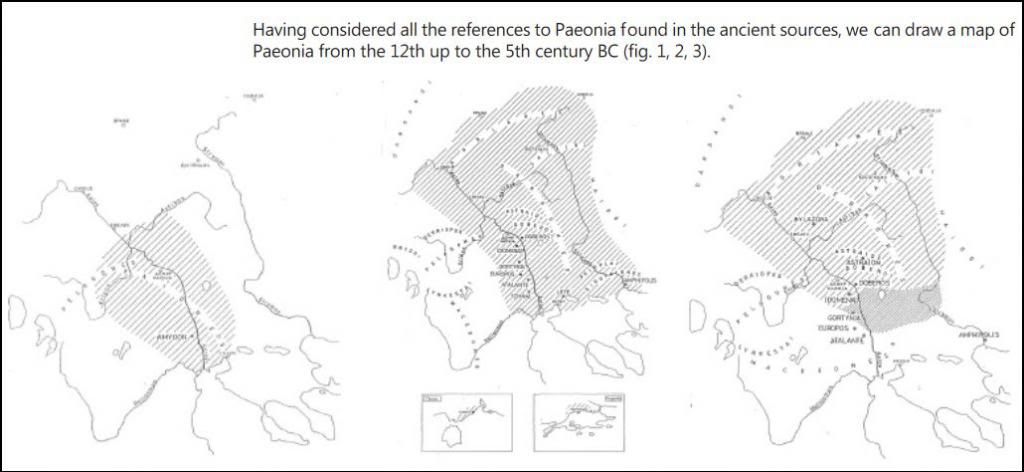

This is the first written document that mentions Paeonians and it is dated in 12th century BC. In the Iliad, Homer left us some important references to Paeonia itself. He is locating the Paeonians on ‘‘the Broad Axius”, mentioning the Paeonian city of Amydon (Homer-Iliad 848-850, H.XIV 287-8). Amydon is also connected with the name of one of the Paeonian leaders, Pyraichmes, who led the Paeonians with curved bows and fighters on carts. The other Paeonian leader Asteropaeus led the Paeonians with long swords and two spears and came from Paeonia, described as hilly and fertile (Homer-Iliad XXI 154-5).

The ‘‘Scholiae”, who presents a critical analysis of Homer’s Iliad, speaks about two Paeonian leaders, but claims that Pyraichmes was their supreme leader. By their explanation Asteropaeus came under Troy later and therefore his name is not included in the list of allies. With this information we can draw certain conclusions about Paeonian tribes from the end of the 2nd millennium BC. Two Paeonian armies appeared as Trojan allies at different times, bearing different arms and coming from different territories (Petrova 1999, 4).

There is an increased amount of information regarding Paeonians in the writings of Herodotus and Thucydides and by their writings we have information about the Paeonian historyand geographical expansion in the 6th and 5th century BC. Thucydides notes that before the arrivalof Macedonians, the Paeonians possessed territories west of Pela and all the way to the sea. According to Thucydides, the upper flow of the Strymon river was settled by the Laeaei and Agrianes andto the west of them were the independent Paeonians. Herodotus mentions two Paeonian tribes, the Siropaeonians and the Paeoplai, and locates them near Pangaeum, the Strymon river and Lake Prasias. He also tries to locate the Doberes but is less precise, placing them in the broad area north of Pangaeum.

The independent Paeonians who lived west of the Agrianes and Laeaei settled the territory west of the upper flow of the Strymon river and probably the territory to the south (Petrova 1999,7). But it cannot be claimed with certainty who were the independent Paeonians. Thucydides’ references (II 96,3) suggest that they were treated as an unconquered segment of the population. This could be a reference to the Derrones, a tribe which settled the regions west and southwest of the Laeaei and Agrianes (Svoronos 1979, 204).

Later geographers provide important clues to the geographical location of Paeonia. Ptolemy locates the Paeonian tribes of Asterai and Ioroi northwest of Pangaeum (Petrova 1999, 8). Describing the Balkans, Strabo says that Paeonia was a hilly territory occupying the central region, separated from Thrace by the Rhodopi Mountains and bordering the lands of the Autariatae and the Dardanians to the north. That is, Dardania bordered Macedonia and Paeonia to the south. Strabo also suggests that Paeonia spread from Pelagonia to Pieria and that a large part of Macedonia was Paeonian, including Amphaxitis on the banks of Axios, Migdonia and Crestonia.

LEFT: FIG. 1 THE PAEO-NIAN TRIBES DURING THE TROYAN WAR 13-12 C. BC MIDDLE: FIG. 2 THE PAEO-NIAN TRIBES IN THE 6THC.BC - CONQUERING OF PERINUTHUS AND ABDERA ON THE THRACIAN COST DURING THE 6 V.BC RIGHT: FIG. 3 THE PAEONIAN TRIBES IN THE BEGINNING OF THE 5 C. BC TERRITORIES CONQUERED BY THE MACEDONIANS AFTER THE 429. C BC

PAEONIAN MINTAGE

The mintage of coins is one of the most important features of Paeonian economical, political and cultural life and it provided Paeonians an access to the civilized Hellenic sphere of influence. The high artistic value in the manufacture of Paeonian coins was a result of an influence of the neighbouring mints from the Hellenized South and a strong political structure and economic potential of the Paeonians. In the period between the 6th and the 3rd century BC, minting became an important element which separated the Paeonians from the barbarian tribes living north of them. Tribes in the region between the upper flow of the Axius and the Strymon rivers and the territories spreading beyond them started minting their own coins very early due to an abundance of ore, silver mines and rivers which contained gold. The closeness of the shore and the developed Hellenic colonies raised the cultural level of these regions, thus providing the conditions for an early beginning of minting (Petrova 1999, 93). The Derrones, Edones, Bizaltes, Oresces, Tynteni, Syrini, Laaei among other, and the cities of Ichnae and Lete were the first tribes to produce coins in the region, starting in the 6th century BC. Homeland of the Derrones is thought to lie between Chalcidice and Dojran in the south and the area between Štip and Kratovo in the north (Petrova 1999, 94). Because of the importanceof the Derrones during the 6th century BC it is thought that they settled the territory between the middle and upper flows of the Vardar and Struma rivers.

Derrone coins were minted in silver after the Eubean standard, mostly in the high denominations of deca and octodrahmas, and weighed between 34 and 41 grams. There are two types of Derronian octodrachmas. The first type shows a pair of oxen pulling a cart and a sun or circle onthe obverse, and quadratum incusum on the reverse, sometimes presented as a swastika (fig. 4).The second type shows a bearded man in an ox-driven cart. A helmet or a symbol of the sun often appears in the upper half, and a palmette or an acanthus in the lower half of the coin (fig. 5). Onthe reverse, there is a triquetrum and tribal affiliation is designated by the legends ΔΕΡΡΟΝΙΚΟΣ, ΔΕΡΡΟΝΙΚΟΝ, ΔΕΡΡΟΝΙ, ΔΕΡΡΟ. Some specimens of derronian octo and deca drachmas discovered in the vicinity of Štip display legends which are probably the names of the Derronian kings eg. ΕΥΕΡΓΕΤΕ(Σ), EX…, ΕΓΚΟ(ΝΟΥ). This suggests that as early as 6th century BC a king headed the Derronian tribal organisation, which was not the case with other contemporary Paeonian tribes. The scarcity of Paeonian money, specimens found on what is presumed to be their principal territory, and, on the other hand, a number of finds in hoards throughout the eastern Mediterranean in Egypt, Jordan, and Syria sufficiently speak about the function of higher values of money minted in the area between the Vardar and the Struma rivers, which spread to the most distant provinces under Persian domination.

However, political changes in the area between the lower flow of Vardar and Struma rivers at the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 5th century, notably the arrival of the Persians and the strengthening of the Macedonians, brought changes into the economic life of tribal organisations.Between 513 and 498 BC these provinces came under the direct Persian rule, as they did during 485 and 480 BC, when the Persian army returned to the Balkans. Under the rule of Alexander I (498-454BC), the Macedonians, who had until then ruled the provinces west of the Vardar, occupied Amphaxitis, Mygdonia and Crestonia as well the area around Pangaeum. It is logical to assume that the tribal economic life, i.e. mintage, which was preconditioned by the ownership of the Pangaeum mines or other resources in the region, definitely disappeared after the Macedonian conquest. After this period, mintage can be assumed only in regions outside of Macedonian control, like the Northern provinces. Therefore, we can presume that the higher values of Archaic-style Derronian coins minted until 480 BC were used for paying taxes to the Persians, while smaller denominations were probably used as a domestic means of payment (Petrova 1994, 9-19).

SPIRITUAL LIFE AND CULTS IN PAEONIA

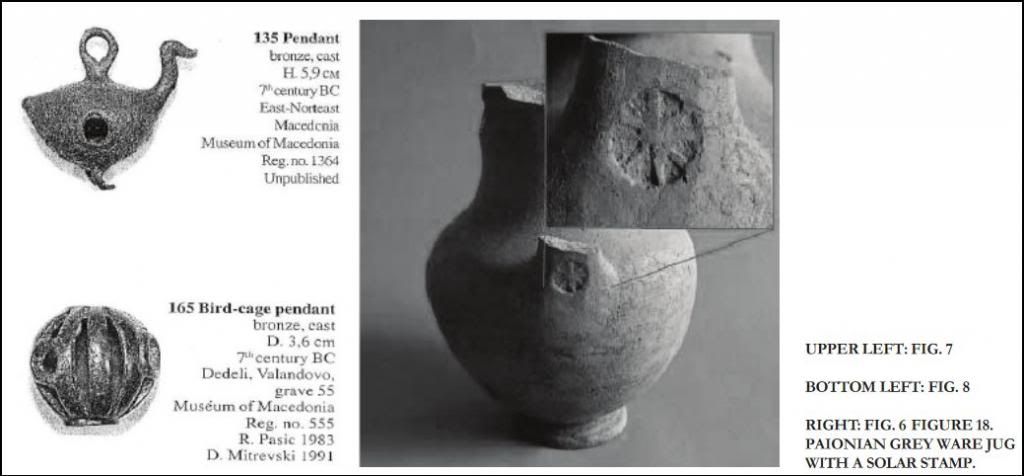

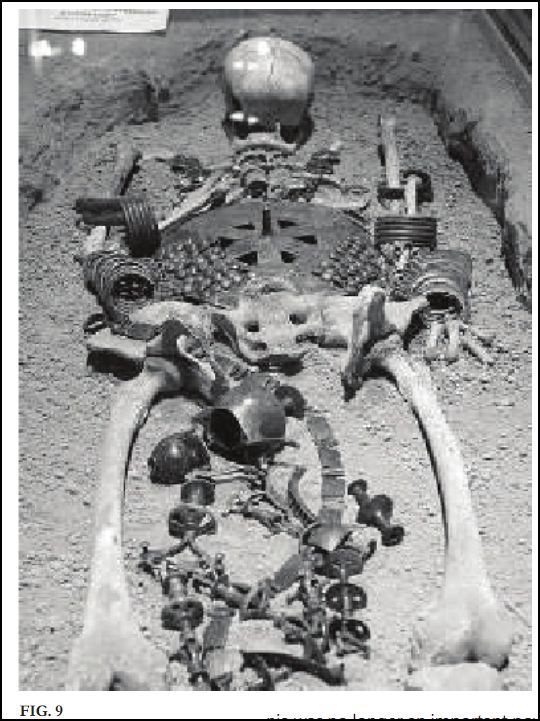

As in the case of all other shapes of Paeonian history and culture, very few records on cults, symbolism and spiritual life have survived. From the north, the influence of the solar cult, sun worship and even elements of solar symbolism spread towards Paeonia as early as the Iron Age and assisted in making it a dominant cult for many centuries to come. Paeonians worshipped the solar cult almost exclusively, it has a central role in Paeonian life. The most commonly worshipped and most simple symbol of solar worship was the image of the circle. There is a reference to this symbol by Maximus of Tyre, a Greek rhetorician from the 2nd century BC, who stated that Paeonians worshipped the sun in the shape of a small disc attached to a long staff (Max.try. II, 8, Petrova 1994 128). In the region of Macedonia, a large number of pendants in the shape of a circle or a circle divided in two, four or six filaments can be found ornamenting bronze artefacts or pottery (fig. 6). Almost every specimen of Derrone coin carries a realistic or stylised sun, which is a strong evidence of the extent to which this symbol was prevalent among Paeonians in the Proto-historic period. In the southern central Balkan region, solar elements, the solar cult in general and the solar symbolism derived from it, are embedded in the spiritual and material culture of Paeonians. Excavations in the central regionof the Vardar valley have revealed that among the grave finds, following elements dominated: bird-shaped pendants (fig. 7), circular objects with variously interpreted functions (fig. 8) and objects withstill unexplained cult content. However, given their ornamentation and solar elements they are undoubtedly linked to the sun cut. In the 1997 excavation at the Lisin Dol site in Marvinci, tomb number 15 (fig. 9), in which a female was buried, contained about 400 finds linked to the sun cult. The tomb contained needles in the shape of spectacles, phalerae, pendants with bird shapes, amber beads,buttons and objects with unknown functions, some of which resembled sun symbols (Petrova 1999,130). These findings suggest that a member of the cult with a key position in Paeonian spiritual lifewas buried in the grave.

By the 5th and 4th century BC, an increased Hellenic influence provoked significant changes in the Paeonian material culture and ultimately resulted in the Paeonian adoption of the Hellenic Pantheon. The worship of only one god from the Pantheon further confirms the domination of the solar cult; Apollo became the principal Paeonian deity in the 5th century BC. The symbol of the sun is obviously connected to Apollo and the same can be said of the sacred cart and the waterfowl (migratory) birds which are linked to Apollo in the legend of the Hyperboreans (Osvalt 1980, 387-388). The Hyperborean cult which also originated in the Bronze Age is also linked to the beginnings of the amber trade, which began in the Central Europe and eventually connected the Greek mainland to the Baltic sea.The first specimens of amber appeared about 1250 BC. Before this date they can be found neither in the inventory of explored sites nor in cemeteries in the south. This shows that the amber trade was established towards the end of the Bronze Age and in the transition period.

SOME MACEDONIAN – PAEONIAN RELATIONS

During the rule of Amyntas I (540-498 BC), Macedonians conquered Paeonian territory west of the Axius river, towards the sea. Later on, Persians conquered the territories around the lower flow of the Strymon river, mentioned in Herodotus’ book V. Probably during the reign of Alexander I (498-454 BC), Paeonians also lost Amphaxitis, Mygdonia and Crestonia as well as the territories around Pangaeum. Havinglost a significant part of its territory of the 5th century BC, Paeonia was no longer an important power in the region. Occupying only the territories surrounding the middle and upper flow of the Axius and the upper flow of the Strymon river.

Events in the regions of Macedonia and Thrace in the 5th century BC, pushed Paeonia into the background and there are no references to it until Sitalces’ conquests when, following the deathof Alexander I, Macedonia lost a part of its territory. During the reign of Perdicas II (450-413 BC) ,Athens were at the peak of its power, and so was the Odrysian kingdom. Led by ambitions, Sitalces attacked Macedonia, taking with him Philip’s son Amyntas (and brother of Perdicas II) to place himon the Macedonian throne (Thuc II, 98, 99, 100).Sitalces’ campaign in Macedonia is of great importance to Paeonian history. During the description of his conquests, the Paeonian tribes of the Laeaei and the Agrianes, who settled the upper flow of the Strymon river and the western most part of Odrysian kingdom, are mentioned forthe first time. When Sitalces left the Odrysian area, the entire population moved with him, includingthe Laeaei and the Agrianes, and crossed over into the unsettled area of the Cercine mountains, situated between the Sinti and the Paeonians. He had taken this route before, when he had conquered the territories of certain Paeonian tribes. Crossing the mountains, he arrived at the Paeonian city of Doberus. He attacked from Doberus and occupied Eidomene, Gortyn and Atalante when the othercites surrendered. He surrounded but did not take Europus and ravaged Mygdonia, Crestonia and Anthemus. However, his campaign was not successful because his army did not have enough food. Furthermore, winter came and Siltaces withdrew after 30 days of conquest. Thucidides’ description of the Odrysian conquest of 430-429 BC contains important reference to the Paeonian tribe of the Laeaei (Thuc II, 96,97), who are not mentioned again by ancient authors, except by Stephen the Byzantine (Steph. Byz 404,14). The disappearance from the historical scene is probably connected with the unification of Paeonian tribes, a union that during the 4th century BC once again experienced a period of rapid economic and political development, power and prosperity.

The other Paeonian tribe, the Agrianes, probably preserved their independence after the fall of Sitalces’ kingdom. During the reign of Filip II, they were already Macedonian allies. The relationships between Macedonians and Agrianes were especially friendly during the reign of AlexanderIII and they were frequently mentioned in Arrian. The Agriane king Langarus showed his friendship towards the Macedonian king for the first time after the campaign against the Triballians in 335 BC.On his return from the Danube, Alexander crossed Agriane and Paeonian land and discovered hewas about to be attacked by the Autariatae. Langarus arrived with his best warriors (hipaspistai) and offered to Alexander to attack them himself, since he believed them to be the least warlike of all Illyrian tribes. After Langarus defeated the Autariatae and ravaged their land, Alexander rewarded him with generous presents and great honours, even promising him his sister Cynane in marriage but after his return from the campaign, Langarus fell ill and died (Arr. I, 5, 1-5). After Alexander’s death there are few references to them, although they took part in many battles as part of the applied forces throughout the entire Hellenistic period. The last mention of Agrianes occurs in 169 BC, when 800 Agrianes who protected Cassandreia are referred to (Liv. XLIV, 7,12,1), and then they disappear from sources, not even receiving mention as mercenaries, troop shipments or tribes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DINDIRF, L. (ed.) 1910, HOMERI ILIAS. – Lipisiae.

ERBSE, H. (ed.) 1969-1975, SCHOLIA GREACE IN HOMERI ILIADEM, vol I,II,III,IV.

JONES, H.J.S., POWEL, J.E. 1942, Oxonii. – In: Thycydides Historiae II, Oxford.

OSVALT, S. 1980, Grcka i rimska mitologija. – Beograd.

PETROVA, E. 1999, Paeonia in the 2nd and the 1st millennia BC. – Skopje.

PETROVA, E. 1994 Oktodrahmata na pajonskoto pleme Deroni. – MNJ, Skopje.

ROSS, A.G. (ed.) 1907, ARRIANI ANABASIS. – Lipisiae

Comment