Do Ancient Greeks have African Origins?

Collapse

X

-

This is a great thread. Shows how diverse the ancient world really was and how impoversihed it became with the rise of monotheism and modern state terror.

Leave a comment:

-

-

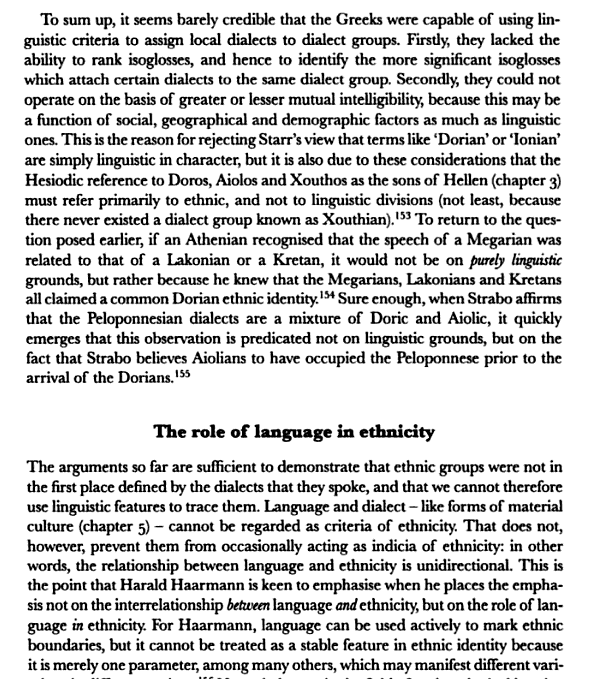

From Jonathan Hall.

The terms 'Hellas' & 'Hellenes':

- 'Hellas' originally denoted a small area south of Thessaly.

- By the end of the seventh century (600's BC), it was employed to describe the whole of mainland Greece.

- By the mid-sixth century (550's BC), it designated the whole of the Greek world.

- The gradual expansion in the geographical scope of the term 'Hellas' tracks almost exactly the increasing membership of the (Religious) Pylaian-Delphic Amphiktyony throughout the Archaic period, suggesting that it was simply a geographical expression employed to describe the aggregation of states that administered the sanctuary of Delphi.

More from J. Hall.

- A number of documents written in the non-Greek language of Eteokretan have come to light.

- Another interesting observation from J. Hall is the following: "Throughout the world and throughout history, multilingualism is the norm rather than the exception." This specifically applies to the ancient Hellenes (..who were a multiethnic multilingual community).

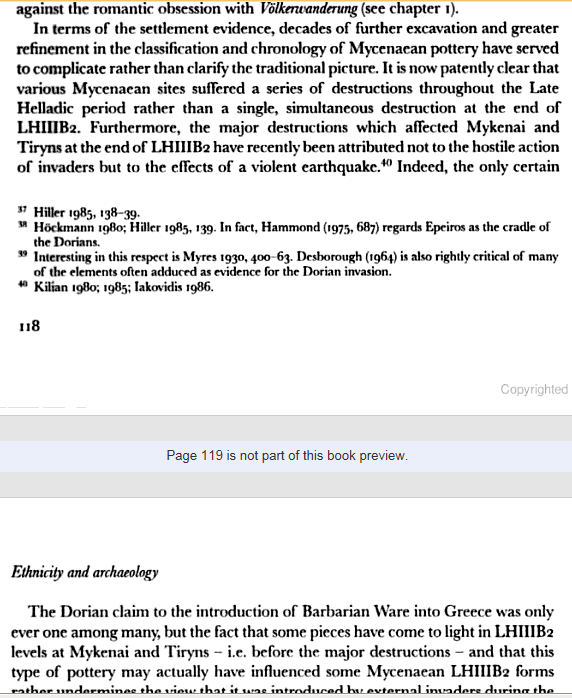

The Dorian invasion:

"It is now patently clear that the various Mycenaean sites suffered a series of destructions throughout the Late Helladic period rather than a single, simultaneous destruction at the end of LHIIIB2. Furthermore, the major destructions which affected Mykenai and Tiryns at the end of LHIIIB2 have recently been attributed not to the hostile action of invaders but to the effects of a violent earthquake."

Last edited by Carlin; 04-27-2013, 12:51 PM.

Last edited by Carlin; 04-27-2013, 12:51 PM.

Leave a comment:

-

-

Majority of inhabitants in Athens were bilingual (if not multilingual).

There was no official policy of enforcing Latin in the (Roman) empire.

Leave a comment:

-

-

The word Athen is pre/non-Greek. My view is there was no such thing as ancient greeks as a homogeneous concept which is alien to how ancient societies actually worked and operated. Usually we are taught the greco-roman view of history filtered through the Roman state form and church dogmatics which is really a false view. What we see in ancient socieities are huge discontinuities at all levels and any attempt to apply modern political or social concepts(based on mostly deterministic methodologies) to their study has to be thrown out the window. The real micro-research shows something very different. So we get a situation where real paleo-identities are denied whereas fabricated ones are considered real and mainstream. I am not sure what they call this phenomenon in the natural sciences, perhaps warping, perhaps illusion. So ancient "greeks" were probably all kinds of different people, which may have included African origins(Egypt, Libya) and also semitic and black sea/anatolian origins. There is evidence of discontinuity, i,e the Dorian invasions, the relation between pre-Greek, Myceanean and the later dialects("ancient greek" as a standard language only really begins with the Alexandrian koine which was a construction and of course the later "modern greek" is an even more removed from the original Hellenic language group) etc, the greek dark age which scholars explain away with straightline extrapolations etc. These could very well be non-greek phenomenon or non-hellenic phenomenon which would just add to the polyglot nature of ancient civilisation formation. One thing is clear to me they were not indigenous to the Balkans or what later became known as "Greece" which were all paleo-Balkan civilisations much older then the later, mostly insular developed "greek" civilisation which was actually a very small plastic cultural world.Last edited by momce; 01-13-2013, 10:19 PM.

Leave a comment:

-

-

there was a thread whether the greeks were black at one point.Evidence shows that the greeks were black like the sudan of afrika.The greeks had the black athena vases depicting blackness.Some writers described macedonians as tall & fair whils't greeks were short & black.I had such a long discussion with a greek agamythae that he refused to beleive that greeks were black but when shown the evidence gis response was" so what if i'm a goddam nigger".Frankly who the fuck cares of what greeks were.A bit of an admissionm to some home truths now & again helps.

Also i read somewhere or another that the word athens is not really a greek word probably stolen from somebody sounds familiar.

Leave a comment:

-

-

Some modern greeks look black actuallyOriginally posted by SirGeorge8600What are you talking about??? Show me a black Greek....and please don't post that picture of the black Greek basketball player who immigrated from Nigeria The average height in Greece is 5 foot 10 for men, and the average with women is five foot four.

The average height in Greece is 5 foot 10 for men, and the average with women is five foot four.

You can find similar numbers throughout Europe.

And no, tallness and hairless-ness is a strong association with African people...when's the last time you saw an African with arm hair, back hair, leg hair, etc.? . I think the mistake here is to confuse black with egyptian, libyan and semitic which is more likely as opposed to pure black which is more nubian.

. I think the mistake here is to confuse black with egyptian, libyan and semitic which is more likely as opposed to pure black which is more nubian.

Leave a comment:

-

-

1) Carian inscriptions from Karabournaki (Salonika)

2) Greek-Carian Bilingual inscriptions from Athens

This book provides the most comprehensive account of the history of the Greek language from its beginnings to late antiquity. In this revised and expanded translation of the Greek original published in 2001, a distinguished international team of scholars goes beyond a merely technical treatment of the subject by examining the language's relationship with politics, society and culture. An attempt is made to cover all aspects of the history of Greek, including those that are usually considered marginal, such as obscene language, the language of the gods and child talk. Other topics which receive particular emphasis are language contact and translation practices in antiquity. The book's clear organisation and concise chapters make it highly readable and accessible to non-specialists, and the text is supported by example passages from primary sources and numerous informative illustrations. It is an essential reference work for all those interested in the history of Greek.

3) Carians/Leleges in Greece (Map)

4) The Land of Ionia: Society and Economy in the Archaic Period, By Alan M. Greaves.

"The predominance of inscriptions from a religious context may be a product of Ionian Greek epigraphic habits at the time (i.e. the use of inscriptions may have been limited to cult practices), or indicate that Greek was not widespread in the wider community.."

5) The First Greek speakers

- A hard task in history is to define who the first Greek speakers were and how they emerged. First of all, the term Greek/Hellenic is something that cannot be used as an ethnonym in the prehistory of the early speakers of this language. Neither can early written forms of Greek set a date to the formation of the ethnogenesis, the language and the culture of these people. In the last centuries many scholars have tried to bound language and archaeology into a date that would signify the so called 'coming of the Greeks'. There are still questions that remain unanswered and others that have more than one explanation.

- From those two theories it is evident that we cannot identify the first Greek speakers nor date their first presence easily. It is like asking where were the English when Julius Caesar invaded Britain? There's no answer to that. To talk about the 'coming of the Greeks' means that we suppose the pre-existence of the Greek language outside Greece, a hypothesis for which there is no evidence. The motherland of the Greek language has always been, the area of the present state of Greece. Just like modern English was formed in England out of Anglo-Saxon heavily contaminated with Norman French and other foreign bodies. The traditional view of waves of Greek-speaking warriors marching down the Balkans to subjugate Greece is an old one.

- The Greeks also knew that some of their countrymen spoke other languages (e.g Eteo-Cretans - meaning true Cretans) or that people they lived with side by side were not originally Greek (e.g the Carians, Leleges).

- In 1963, Chadwick was the first to propose that the Greek language did not exist as we know it before the 20th century BC, but was formed by the mixture of an indigenous populations with invaders who spoke another PIE language. When these newcomers (mello-Greeks) reached Greece, they mixed with the previous inhabitants, whom they succeeded in subjugating, and borrowed from them many words for unfamiliar objects. The mispronunciation of the PIE words by those aboriginals led to permanent changes in the phonetics. Both the indigenous inhabitants and the newcomers started to form a group that in the future would become the Greeks. Future discoveries might throw some light into the Greek language prehistory. What is certain right now, is that the first Greek speakers had a multi-ethnic/lingual prehistory. In other words the fusion of cultures and languages of the Greek mainland and the Aegean starting from the neolithic period until the Trojan war has been the mother of the Hellenic tongue.

What is certain right now, is that the first Greek speakers had a multi-ethnic/lingual prehistory. In other words the fusion of cultures and languages of the Greek mainland and the Aegean starting from the neolithic period until the Trojan war has been the mother of the Hellenic tongue.

Leave a comment:

-

-

the problem is to get that greek jack in the box out of Macedonia to get that hunchback of notre dame out of Macedonia..holy shit greece are like the guy riding the bicycle with popcorn and candy thinking everywhere he goes is greece and trying to trap people in his cage hahahaLast edited by momce; 12-25-2012, 10:36 PM.

Leave a comment:

-

-

Excerpts from Hellenicity by Jonathan Hall (2005)

In this book Jonathan Hall seeks to demonstrate that the ethnic groups of ancient Greece, like many ethnic groups throughout the world today, were not ultimately racial, linguistic, religious or cultural groups, but social groups whose 'origins' in extraneous territories were just as often imagined as they were real. Adopting an explicitly anthropological point of view, he examines the evidence of literature, archaeology and linguistics to elucidate the nature of ethnic identity in ancient Greece. Rather than treating Greek ethnic groups as 'natural' or 'essential' - let alone 'racial' - entities, he emphasises the active, constructive and dynamic role of ethnography, genealogy, material culture and language in shaping ethnic consciousness. An introductory chapter outlines the history of the study of ethnicity in Greek antiquity.

Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity

In today's cosmopolitan world, ethnic and national identity has assumed an ever-increasing importance. But how is this identity formed, and how does it change over time? With Hellenicity, Jonathan M. Hall explores these questions in the context of ancient Greece, drawing on an exceptionally wide range of evidence to determine when, how, why, and to what extent the Greeks conceived themselves as a single people. Hall argues that a subjective sense of Hellenic identity emerged in Greece much later than is normally assumed. For instance, he shows that the four main ethnic subcategories of the ancient Greeks—Akhaians, Ionians, Aiolians, and Dorians—were not primordial survivals from a premigratory period, but emerged in precise historical circumstances during the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. Furthermore, Hall demonstrates that the terms of defining Hellenic identity shifted from ethnic to broader cultural criteria during the course of the fifth century B.C., chiefly due to the influence of Athens, whose citizens formulated a new Athenoconcentric conception of "Greekness."

"Although the Greeks themselves believed in polygenetic origins within

the Balkan peninsula in Greece, the discovery of the Indo-European

language group prompted scholars to view Greek speakers as immigrants

from an original Indo-European homeland. Furthermore, the fact that

Greek civilization is known predominantly—and, prior to the emergence

of the discipline of archaeology, exclusively—through its literary

remains has tented to promote the Greek language as the quintessential

expression of Greekness. The result is that a horizon has been drawn

between a pre-Greek chronological phase and a properly Greek era,

signaled by the arrival of the first Greek speakers. Chapter 2 charts

the various attempts that have been made to date this arrival by means

of perceived disjuncture in the archaeological record and argues,

firstly, that these supposed cultural breaks are becoming ever more

illusory as our archaeological knowledge increases and, secondly that

the very assumptions that apparent material innovations should signal

the arrival of a new language and that a linguistic group necessarily

equates with a self-conscious ethnic group are, on the basis of

comparative anthropological evidence questionable (Hall 2005, p. 5)."

"More importantly, the biblical account of unilineal or monogenetic

origins in the Near East dictated that the ancestors of the Greeks

must have arrived from OUTSIDE Greece (Hall 2005, p. 37, emphasis in

the original)."

"Although claims for a northern European origin have not been entirely

abated today, they are largely outnumbered by proposals for an

Indo-European Urheimat in either the steppes of Southern Russia or,

more recently, Anatolia. The debate is still far from being resolved

to universal satisfaction, but with regard to specifically Greek

origins the question most frequently posed has not been "from where?"

but rather "When?" (Hall 2005, p. 28)."

"Schmidt (proponent of the wave model) himself did not question the

existence of an original PIE languages, but the Russian linguist

Nikolai Trubetskoy (1939) raised the possibility that originally

dissimilar "Indo-European" languages could have gradually come to

resemble one another through repeated contact and borrowing. Parallel

examples of this phenomenon are offered by the languages of the

Balkans; the Chinese, Thai and Vietnamese languages in southeast Asia;

the Indo-European, Dravidian and Munda languages of the Indian

subcontinent; and the Indo-European and Caucasian leagues of the Black

Sea and Caspian areas. The question is whether the undeniably closer

and more numerous correspondences among Indo-European languages can

similarly be explained by an exceptionally long period of contact an

development, but either way it is clear that linguistic innovation

need to require the sort of mass immigration that archeologist have

sought in the material record (Hall 2005, p. 44, parenthesis added)."

"The whole debate on the "coming of the Greeks" has been characterized

by the repeated tendency to confuse emic (internal/subjective) and

etic (external/objective) categories. Even if we are prepared to

accept that a number—be it large or small—of Indo-European speakers

arrived in the Greek mainland at a certain point in time and imposed

their language on the substrate language of their predecessors, that

does not in itself indicate the commencement of Hellenic identity as

the Greeks themselves conceived it. The history of a language or of

cultural practices is not necessarily the same as the history of the

people who are later identified—and identify themselves—with these

markers (Hall 2005, p. 45)."

Hall, J. M. (2005). Hellenicity: between ethnicity and culture.

Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31330-6

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Journal of Interdisciplinary History 34.1 (2003) 65-66

Hellenicity: Between Ethnicity and Culture. By Jonathan M. Hall (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2002) 312pp. $50.00

In a famous passage (Histories, 8.144), Herodotus has the Athenians chastise the Spartans for fearing that Athens might capitulate to the Persians. Several deterrents, according to the Athenians, keep them from betraying Greece—the places of worship that the Persians had destroyed andthe elements constituting a "common Greekness" (to Hellenikon)—common blood and language, common shrines to the gods, common sacrifices, and common customs. This seems to be straightforward testimony to the ancient Greek conception of Hellenic ethnicity, but Hall demonstrates that communally shared Panhellenic identity was unstable and, at most times, less salient than other collective identities, especially in pre-classical Greece apart from Athens.

This study traces the formation of a collective Hellenic identity in Greek antiquity, referring throughout by neologism to ancient Greek ethnic consciousness as "Hellenicity." Hall begins by setting out his methodological and theoretical positions on the study of ethnic identity. For him, ethnicity represents a constructivist "imagined community," not any primordial Stammbaum, and ethnicity "denotes both the self-consciousness of belonging to an ethnic group ('ethnic identity') and the dynamic process that structures, and is structured by, ethnic groups in social interaction with one another." The most important aspects of ethnic self-ascription are mythic common descent and kinship, an association with a geographical locality or region, and a sense of common historical experience. Above all, ethnicity is attitudinal and selective, and it is strategically employed in particular historical configurations in the interests of its constituency.

Hall takes up the question of ancient Greek origins, offering a good historical synthesis of modern archaeological and linguistic work on the problem of when Greek-speaking peoples first arrived in Greece. But this question is of peripheral importance to Hall's study. He argues that Greek-speakers' penetration into the Greek peninsula came gradually over an extended period of time, and that the idea of a massive population influx of Greek speakers is untenable. The main ethnic sub-categories of the ancient Greeks—Achaeans, Ionians, Aiolians, and Dorians—only emerged in local conditions during the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. Panhellenism was a sporadic and ephemeral force in ancient Greece. It peaked under extraordinary circumstances—prospects for united aggression, the threatened security of Hellas, or international crisis for the collective Greek city-states. Hall suggests that we look to the great athletic festivals for origins; in this context, Hellenism may have been an aggregrative ethnicity that operated across geographically contiguous regions to weld together a transregional aristocracy against lesser status groups. "Hellenicity" clearly emerges only in the fifth century B.C.E., and then it was largely the production of imperial Athens, which acted as "the new self-appointed arbiter of cultural authenticity." Hellenic identity thus came to be measured increasingly in terms of culture and education rather than of putative descent groups through a process that reached its completion during the Hellenistic age.

Craige B. Champion

Syracuse UniversityLast edited by Carlin; 12-24-2012, 04:39 PM.

Leave a comment:

-

-

So there is no clear recipe for the archetypal Hellene against which the non-Hellene can be measured and weighed. Both descriptors must have changed over time and space, in reaction to different stimuli. As a category, "Hellene" (like "Phoenician") is unstable, variously applying some combination of cultural behaviors, kinship ties and general genealogical ties, quasi-national identity, intra-Hellenic identity, and so on, depending on context. Inclusion or exclusion as a Hellene is not necessarily located in clear-cut difference or absolute otherness. Rather, difference was probably located within categories of what was apparently the same. Likewise, cultural conjunctions "serve to underscore, not to undermine" cultural distinctiveness.

Leave a comment:

-

-

I understand ethnicity to be a subjective social concept established through "fictive kinship and descent, common history and a specific homeland". Ethnic identity was self-consciously asserted through myth, genealogies and other variables of collective identity.Last edited by Carlin; 12-22-2012, 01:58 AM.

Leave a comment:

-

-

"Hellenization" and Southern Phoenicia: Reconsidering the Impact of Greece Before Alexander, by Susan Rebecca Martin

Page 30-31:

- Jonathan Hall states that self-awareness arose on the mainland from inter-Greek relationships and only as early as the sixth century.

- Greek self-awareness was most likely cemented in, or at least was developed by, its confrontation with the Persians. It was in the fifth century that the idea of Hellenism really began to take shape, around the same time that the Hellenization of Phoenicia allegedly began. Several recent studies have rightly taken this idea to task, questioning the extent to which Greeks considered themselves a national group and challenging the Greek/anti-Greek or "oppositional" approach so often associated with the idea that the Persian Wars were the major catalyst for the creation of Hellenic identity.

- In Greece, we can speak of various autonomous groups emerging from the Dark Ages that only sometimes (even rarely) recognized their commonality through culture, or Hellenism.

Page 34:

- Through the example of language, a process is suggested which "barbarians" could become increasingly at "being Greek". Hellenes and barbarians are not perceived as antithetical but as different points on the same continuum. They represent different (cultural) possibilities.

Page 36:

- A plurality of models existed. These models seem to have been quite fluid and could be interpreted and reinterpreted at will - even by the same author in the same book.

Page 38-40:

- According to Claudius Iolaus, the "Dorians" were considered Phoenicians. In the passage, "Phoenician" is not ethnically antithetical to (the unstated) "Hellene" but is still important to describing "Dorian" identity.

- In the case of the Phoenicians "Dorians" in Claudius Iolaus, I think it better to understand "Phoenician" and "Hellene" as cultural groups encompassing various identities and ethnicities (etc.), some of which were shared.

- Instead of seeing neat categories of Greek/non-Greek, or imagining "barbaroi" becoming Hellenes by moving through a checklist of Greek traits, we see that there were multiple degrees of interaction with a variety of outcomes in different periods and regions. One could speak Greek, or be tied ethnically to some Greeks, while still maintaining an Amphilochian, Karian or Phoenician identity.

- Greek material culture appears in Phoenicia and exists way before Alexander's conquest.

Last edited by Carlin; 12-22-2012, 01:48 AM.

Leave a comment:

-

-

yes hellenes seems to be more an economic-cultural phenomenon..some observations,:

(1) there seems to be a huge gap between "greek" tribal development and language development-is it dialectical? if not it cannot be something real but invented

(2) greeks are mostly an urban phenomenon even in the ancient world

(3) they live mostly around coastal areas in urban settlements, based on sea-borne commerce

(4) the countryside is not "greek", even the cities have mixed populations many of them obviously of non-greek origin..the settlements themselves may or may not be of greek origin but may have been taken over

(5) the ancient greece borrows alot of things from other cultures especially Egyptian, Libyan etc

(6) Christianity and modern state machines allowed people to be assimilated faster and easier and made them forget their origins(related to Romes destruction of ancient tribal structures)

(7) capitalism made the entire process of destruction, assimilation more efficient

(8)hellenes have seems no connection to the land whatsoever, in fact they are something of an oddity in the entire Balkan-the ancient myths about origins are most likely lies and inventions to justify politics

(9) it explains why there is no such thing as a modern greek folk culture since its all borrowed from other peoples, probably the original inhabitants of the Balkan and also the Turks-i.e the real greek petitbourgeois culture probably died with the ancient world, "hellenes" were a superstructural phenomenon that disappeared when the socio-economic conditions dissappeared

So there is no homogeneity there or political-cultural and geographic continuity but an attempt to force things in ones favour for various reasons. So there is alot to retrieved in many senses.

Leave a comment:

-

-

momce you hit the nail on the head there is no such thing as a hellene it's just a play on words.The greeks haven't worked out yet of who they are & have resorted to hellene as termilogy not an ethnic denotation.

Leave a comment:

-

Leave a comment: