Again,provocateurs inflating an issue to the extent of mass hysteria for propaganda purposes.

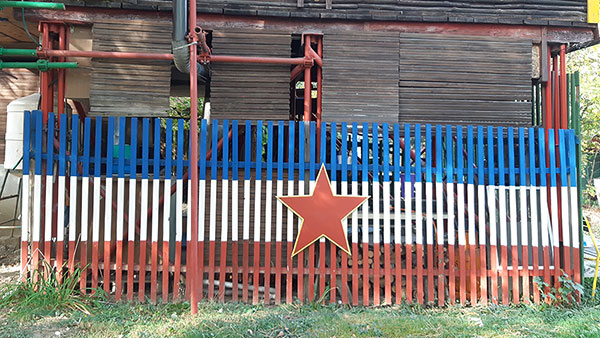

The referendum was whether or not a specific date should keep being celebrated as a national holiday in the mostly Sebian-populated entity of the federation.

This was presented (overblown) in the bosniak-croat entity as the first step towards a referendum for independence of republika Srpska from Bosnia.Like,if Bosnia allows this referendum this would lead to an attempt of separation by the Serbs.

I believe this is just a "pulse check" by the Russian-American propaganda machinery aimed at the Bosnian citizens.

The referendum was whether or not a specific date should keep being celebrated as a national holiday in the mostly Sebian-populated entity of the federation.

This was presented (overblown) in the bosniak-croat entity as the first step towards a referendum for independence of republika Srpska from Bosnia.Like,if Bosnia allows this referendum this would lead to an attempt of separation by the Serbs.

I believe this is just a "pulse check" by the Russian-American propaganda machinery aimed at the Bosnian citizens.

Comment