Link: https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-47258809

By ratifying an agreement with the newly renamed Republic of North Macedonia, Greece has implicitly recognised the existence of a Macedonian language and ethnicity. And yet it has denied the existence of its own Macedonian minority for decades, says Maria Margaronis. Will something now change?

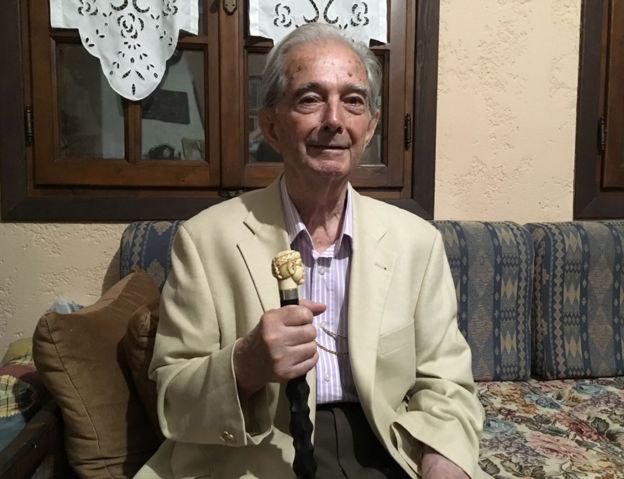

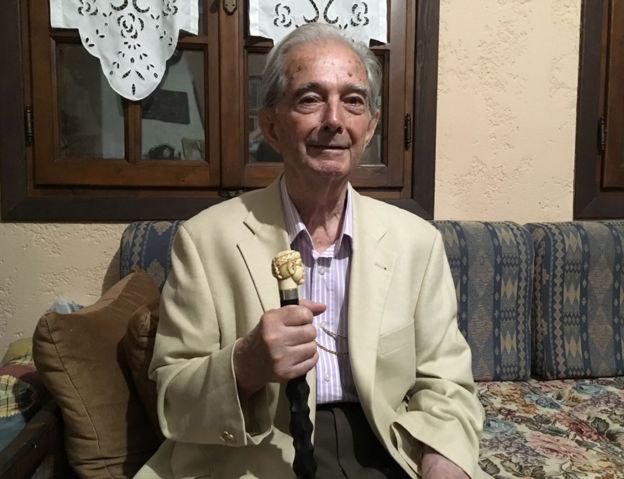

Mr Fokas, 92, stands straight as a spear in his tan leather brogues and cream blazer, barely leaning on the ebony and ivory cane brought from Romania by his grandfather a century ago. His mind and his memory are as sharp as his outfit.

A retired lawyer, Mr Fokas speaks impeccable formal Greek with a distinctive lilt: his mother tongue is Macedonian, a Slavic language related to Bulgarian and spoken in this part of the Balkans for centuries. At his son's modern house in a village in northern Greece, he takes me through the painful history of Greece's unrecognised Slavic-speaking minority.

Mr Fokas takes care to emphasise from the start that he is both an ethnic Macedonian and a Greek patriot. He has good reason to underline his loyalty: for almost a century, ethnic Macedonians in Greece have been objects of suspicion and, at times, persecution, even as their presence has been denied by almost everyone.

Most are reluctant to speak to outsiders about their identity. To themselves and others, they're known simply as "locals" (dopyi), who speak a language called "local" (dopya). They are entirely absent from school history textbooks, have not featured in censuses since 1951 (when they were only patchily recorded, and referred to simply as "Slavic-speakers"), and are barely mentioned in public. Most Greeks don't even know that they exist.

That erasure was one reason for Greece's long-running dispute with the former Yugoslav republic now officially called the Republic of North Macedonia. The dispute was finally resolved last month by a vote in the Greek parliament ratifying (by a majority of just seven) an agreement made last June by the countries' two prime ministers. When the Greek Prime Minster, Alexis Tsipras, referred during the parliamentary debate to the existence of "Slavomacedonians" in Greece - at the time of World War Two - he was breaking a long-standing taboo.

The use of the name "Macedonia" by the neighbouring nation state implicitly acknowledges that Macedonians are a people in their own right, and opens the door to hard questions about the history of Greece's own Macedonian minority.

When Mr Fokas was born, the northern Greek region of Macedonia had only recently been annexed by the Greek state. Until 1913 it was part of the Ottoman Empire, with Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia all wooing its Slavic-speaking inhabitants as a means to claiming the territory. It was partly in reaction to those competing forces that a distinctive Slav Macedonian identity emerged in the late 19th and early 20th Century. As Mr Fokas's uncle used to say, the family was "neither Serb, nor Greek, nor Bulgarian, but Macedonian Orthodox".

In the end, the Slav Macedonians found themselves divided between those three new states. In Greece, some were expelled; those who remained were pushed to assimilate. All villages and towns with non-Greek names were given new ones, chosen by a committee of scholars in the late 1920s, though almost a century later some "locals" still use the old ones.

In 1936, when Mr Fokas was nine years old, the Greek dictator Ioannis Metaxas (an admirer of Mussolini) banned the Macedonian language, and forced Macedonian-speakers to change their names to Greek ones.

Mr Fokas remembers policemen eavesdropping on mourners at funerals and listening at windows to catch anyone speaking or singing in the forbidden tongue. There were lawsuits, threats and beatings.

Women - who often spoke no Greek - would cover their mouths with their headscarves to muffle their speech, but Mr Fokas's mother was arrested and fined 250 drachmas, a big sum back then.

"Slavic-speakers suffered a lot from the Greeks under Metaxas," he says. "Twenty people from this village, the heads of the big families, were exiled to the island of Chios. My father-in-law was one of them." They were tortured by being forced to drink resin oil, a powerful laxative.

When Germany, Italy and Bulgaria invaded Greece in 1941, some Slavic-speakers welcomed the Bulgarians as potential liberators from Metaxas's repressive regime. But many soon joined the resistance, led by the Communist Party (which at that time supported the Macedonian minority) and continued fighting with the Communists in the civil war that followed the Axis occupation. (Bulgaria annexed the eastern part of Greek Macedonia from 1941 to 1944, committing many atrocities; many Greeks wrongly attribute these to Macedonians, whom they identify as Bulgarians.)

When the Communists were finally defeated, severe reprisals followed for anyone associated with the resistance or the left.

"Macedonians paid more than anyone for the civil war," Mr Fokas says. "Eight people were court-martialled and executed from this village, eight from the next village, 23 from the one opposite. They killed a grandfather and his grandson, just 18 years old."

Mr Fokas was a student in Thessaloniki then - but he too was arrested and spent three years on the prison island of Makronisos, not because of anything he'd done but because his mother had helped her brother-in-law escape through the skylight of a cafe where he was being held.

Most of the prisoners on Makronisos were Greek leftists, and were pressed to sign declarations of repentance for their alleged Communist past. Those who refused were made to crawl under barbed wire, or beaten with thick bamboo canes. "Terrible things were done," Mr Fokas says. "But we mustn't talk about them. It's an insult to Greek civilisation. It harms Greece's good name."

Tens of thousands of fighters with the Democratic Army, about half of them Slavic-speakers, went into exile in Eastern bloc countries during and after the civil war. About 20,000 children were taken across the border by the Communists, whether for their protection or as reserve troops for a future counter-attack.

Many Slavic-speaking civilians also went north for safety. Entire villages were left empty, like the old settlement of Krystallopigi (Smrdes in Macedonian) near the Albanian border, where only the imposing church of St George stands witness to a population that once numbered more than 1,500 souls.

In 1982, more than 30 years after the conflict's end, Greece's socialist government issued a decree allowing civil war refugees to return - but only those who were "of Greek ethnicity". Ethnic Macedonians from Greece remained shut out of their country, their villages and their land; families separated by the war were never reunited.

Mr Fokas's father-in-law and brother-in-law both died in Skopje. But, he points out, that decree tacitly recognised that there were ethnic Macedonians in Greece, even though the state never officially recognised their existence: "Those war refugees left children, grandchildren, fathers, mothers behind. What were they, if not Macedonians?"

It's impossible accurately to calculate the number of Slavic-speakers or descendants of ethnic Macedonians in Greece. Historian Leonidas Embiricos estimates that more than 100,000 still live in the Greek region of Macedonia, though only 10,000 to 20,000 would identify openly as members of a minority - and many others are proud Greek nationalists.

The Macedonian language hasn't officially been banned in Greece for decades, but the fear still lingers. A middle-aged man I met in a village near the reed beds of Lake Prespa, where the agreement between Greece and the North Macedonian republic was first signed last June, explained that this fear is passed down through the generations. "My parents didn't speak the language at home in case I picked it up and spoke it in public. To protect me. We don't even remember why we're afraid any more," he said. Slowly the language is dying. Years of repression pushed it indoors; assimilation is finishing the job.

And yet speaking or singing in Macedonian can still be cause for harassment. Mr. Fokas' son is a musician; he plays the haunting Macedonian flute for us as his own small son looks on. He and a group of friends used to host an international music festival in the village square, with bands from as far away as Brazil, Mexico and Russia.

"After those bands had played we'd have a party and play Macedonian songs," he says. "None of them were nationalist or separatist songs - we would never allow that. But in 2008, just as we were expecting the foreign musicians to arrive, the local authority suddenly banned us from holding the festival in the square, even though other people - the very ones who wanted us banned - still hold their own events there."

At the last minute, the festival was moved to a field outside the village, among the reeds and marshes, without proper facilities - which, Mr Fokas's son points out, only made Greece look bad.

"And do you know why the songs are banned in the square but not the fields outside?" his father adds. "Because around the square there are cafes, and local people could sit there and watch and listen secretly. But outside the village they were afraid to join in - they would have drawn attention to themselves by doing that."

The ratification of Greece's agreement with the Republic of North Macedonia - and its implicit recognition of a Macedonian language and ethnicity - is a major political breakthrough which should help to alleviate such fears. But the process has also sparked new waves of anger and anxiety, with large, sometimes violent protests opposing the agreement, supported by parts of the Orthodox church.

An election is due before the end of the year. Greece's right-wing opposition has been quick to capitalise on nationalist sentiments, accusing the Syriza government of treason and betrayal. For Greece's Slavic-speakers, who have long sought nothing more than the right to cultural expression, the time to emerge from the shadows may not quite yet have arrived.

Mr Fokas has been referred to by his first name to protect his identity

Mr Fokas, 92, stands straight as a spear in his tan leather brogues and cream blazer, barely leaning on the ebony and ivory cane brought from Romania by his grandfather a century ago. His mind and his memory are as sharp as his outfit.

A retired lawyer, Mr Fokas speaks impeccable formal Greek with a distinctive lilt: his mother tongue is Macedonian, a Slavic language related to Bulgarian and spoken in this part of the Balkans for centuries. At his son's modern house in a village in northern Greece, he takes me through the painful history of Greece's unrecognised Slavic-speaking minority.

Mr Fokas takes care to emphasise from the start that he is both an ethnic Macedonian and a Greek patriot. He has good reason to underline his loyalty: for almost a century, ethnic Macedonians in Greece have been objects of suspicion and, at times, persecution, even as their presence has been denied by almost everyone.

Most are reluctant to speak to outsiders about their identity. To themselves and others, they're known simply as "locals" (dopyi), who speak a language called "local" (dopya). They are entirely absent from school history textbooks, have not featured in censuses since 1951 (when they were only patchily recorded, and referred to simply as "Slavic-speakers"), and are barely mentioned in public. Most Greeks don't even know that they exist.

That erasure was one reason for Greece's long-running dispute with the former Yugoslav republic now officially called the Republic of North Macedonia. The dispute was finally resolved last month by a vote in the Greek parliament ratifying (by a majority of just seven) an agreement made last June by the countries' two prime ministers. When the Greek Prime Minster, Alexis Tsipras, referred during the parliamentary debate to the existence of "Slavomacedonians" in Greece - at the time of World War Two - he was breaking a long-standing taboo.

The use of the name "Macedonia" by the neighbouring nation state implicitly acknowledges that Macedonians are a people in their own right, and opens the door to hard questions about the history of Greece's own Macedonian minority.

When Mr Fokas was born, the northern Greek region of Macedonia had only recently been annexed by the Greek state. Until 1913 it was part of the Ottoman Empire, with Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia all wooing its Slavic-speaking inhabitants as a means to claiming the territory. It was partly in reaction to those competing forces that a distinctive Slav Macedonian identity emerged in the late 19th and early 20th Century. As Mr Fokas's uncle used to say, the family was "neither Serb, nor Greek, nor Bulgarian, but Macedonian Orthodox".

In the end, the Slav Macedonians found themselves divided between those three new states. In Greece, some were expelled; those who remained were pushed to assimilate. All villages and towns with non-Greek names were given new ones, chosen by a committee of scholars in the late 1920s, though almost a century later some "locals" still use the old ones.

In 1936, when Mr Fokas was nine years old, the Greek dictator Ioannis Metaxas (an admirer of Mussolini) banned the Macedonian language, and forced Macedonian-speakers to change their names to Greek ones.

Mr Fokas remembers policemen eavesdropping on mourners at funerals and listening at windows to catch anyone speaking or singing in the forbidden tongue. There were lawsuits, threats and beatings.

Women - who often spoke no Greek - would cover their mouths with their headscarves to muffle their speech, but Mr Fokas's mother was arrested and fined 250 drachmas, a big sum back then.

"Slavic-speakers suffered a lot from the Greeks under Metaxas," he says. "Twenty people from this village, the heads of the big families, were exiled to the island of Chios. My father-in-law was one of them." They were tortured by being forced to drink resin oil, a powerful laxative.

When Germany, Italy and Bulgaria invaded Greece in 1941, some Slavic-speakers welcomed the Bulgarians as potential liberators from Metaxas's repressive regime. But many soon joined the resistance, led by the Communist Party (which at that time supported the Macedonian minority) and continued fighting with the Communists in the civil war that followed the Axis occupation. (Bulgaria annexed the eastern part of Greek Macedonia from 1941 to 1944, committing many atrocities; many Greeks wrongly attribute these to Macedonians, whom they identify as Bulgarians.)

When the Communists were finally defeated, severe reprisals followed for anyone associated with the resistance or the left.

"Macedonians paid more than anyone for the civil war," Mr Fokas says. "Eight people were court-martialled and executed from this village, eight from the next village, 23 from the one opposite. They killed a grandfather and his grandson, just 18 years old."

Mr Fokas was a student in Thessaloniki then - but he too was arrested and spent three years on the prison island of Makronisos, not because of anything he'd done but because his mother had helped her brother-in-law escape through the skylight of a cafe where he was being held.

Most of the prisoners on Makronisos were Greek leftists, and were pressed to sign declarations of repentance for their alleged Communist past. Those who refused were made to crawl under barbed wire, or beaten with thick bamboo canes. "Terrible things were done," Mr Fokas says. "But we mustn't talk about them. It's an insult to Greek civilisation. It harms Greece's good name."

Tens of thousands of fighters with the Democratic Army, about half of them Slavic-speakers, went into exile in Eastern bloc countries during and after the civil war. About 20,000 children were taken across the border by the Communists, whether for their protection or as reserve troops for a future counter-attack.

Many Slavic-speaking civilians also went north for safety. Entire villages were left empty, like the old settlement of Krystallopigi (Smrdes in Macedonian) near the Albanian border, where only the imposing church of St George stands witness to a population that once numbered more than 1,500 souls.

In 1982, more than 30 years after the conflict's end, Greece's socialist government issued a decree allowing civil war refugees to return - but only those who were "of Greek ethnicity". Ethnic Macedonians from Greece remained shut out of their country, their villages and their land; families separated by the war were never reunited.

Mr Fokas's father-in-law and brother-in-law both died in Skopje. But, he points out, that decree tacitly recognised that there were ethnic Macedonians in Greece, even though the state never officially recognised their existence: "Those war refugees left children, grandchildren, fathers, mothers behind. What were they, if not Macedonians?"

It's impossible accurately to calculate the number of Slavic-speakers or descendants of ethnic Macedonians in Greece. Historian Leonidas Embiricos estimates that more than 100,000 still live in the Greek region of Macedonia, though only 10,000 to 20,000 would identify openly as members of a minority - and many others are proud Greek nationalists.

The Macedonian language hasn't officially been banned in Greece for decades, but the fear still lingers. A middle-aged man I met in a village near the reed beds of Lake Prespa, where the agreement between Greece and the North Macedonian republic was first signed last June, explained that this fear is passed down through the generations. "My parents didn't speak the language at home in case I picked it up and spoke it in public. To protect me. We don't even remember why we're afraid any more," he said. Slowly the language is dying. Years of repression pushed it indoors; assimilation is finishing the job.

And yet speaking or singing in Macedonian can still be cause for harassment. Mr. Fokas' son is a musician; he plays the haunting Macedonian flute for us as his own small son looks on. He and a group of friends used to host an international music festival in the village square, with bands from as far away as Brazil, Mexico and Russia.

"After those bands had played we'd have a party and play Macedonian songs," he says. "None of them were nationalist or separatist songs - we would never allow that. But in 2008, just as we were expecting the foreign musicians to arrive, the local authority suddenly banned us from holding the festival in the square, even though other people - the very ones who wanted us banned - still hold their own events there."

At the last minute, the festival was moved to a field outside the village, among the reeds and marshes, without proper facilities - which, Mr Fokas's son points out, only made Greece look bad.

"And do you know why the songs are banned in the square but not the fields outside?" his father adds. "Because around the square there are cafes, and local people could sit there and watch and listen secretly. But outside the village they were afraid to join in - they would have drawn attention to themselves by doing that."

The ratification of Greece's agreement with the Republic of North Macedonia - and its implicit recognition of a Macedonian language and ethnicity - is a major political breakthrough which should help to alleviate such fears. But the process has also sparked new waves of anger and anxiety, with large, sometimes violent protests opposing the agreement, supported by parts of the Orthodox church.

An election is due before the end of the year. Greece's right-wing opposition has been quick to capitalise on nationalist sentiments, accusing the Syriza government of treason and betrayal. For Greece's Slavic-speakers, who have long sought nothing more than the right to cultural expression, the time to emerge from the shadows may not quite yet have arrived.

Mr Fokas has been referred to by his first name to protect his identity

Comment